East Africa has an abduction problem. In Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania, illegal detention by the police, mysterious disappearances, and government kidnappings have become the norm.

But these individual countries aren’t operating in isolation. An activist might disappear in Kenya, then reappear in a military prison in Uganda. In January a woman in Kenya was abducted and set to be handed over to Tanzanian police, before human rights groups intervened.

Last year Kenya reported 80 political abductions in 6 months. Tanzania has had 60 ‘reported’ abductions in the past 2 years. And Uganda registered over 1000 abductions during the 2021 elections alone.

So why do East Africa’s police so often practice unlawful detention?

Colonial Legacy?

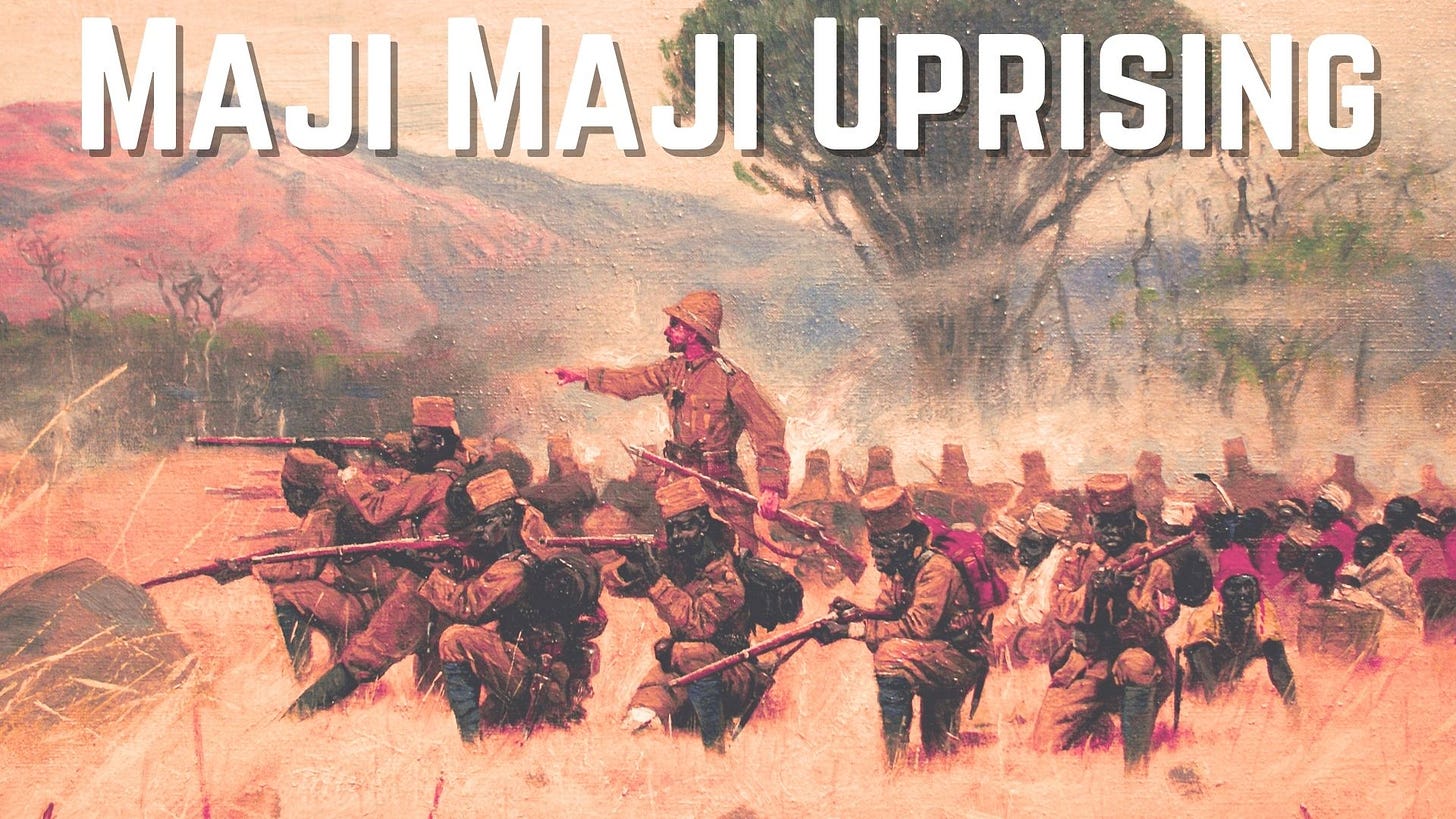

British colonialism in East Africa was a messy business. Tanzania, for example, started life as a German colony. Governor von Gotzen was a military man and saw little difference between the police and the army. During the Maji Maji rebellion, when villages refused to grow cotton, von Gotzen used soldiers to try and enforce colonial law. When the situation descended into open war, he burnt huts and fields, leaving hundreds of thousands dead by famine. From very early on in East Africa, colonial ‘law’ seemed to be an extension of the arbitrary demands of the most powerful.

In a sense Maji Maji was exceptional. British colonial police usually prioritized keeping the peace. Empires can’t afford too many rebellions. As cities like Nairobi and Dar es Salam grew so did their law enforcement. Rural areas were mostly left alone.

It was in the 1950s that colonial police in East Africa found themselves in the spotlight. As frustration over colonialism grew the colonial government used police to monitor, arrest, and interrogate political activists.

The most famous example of this came in Kenya where a police team (the Special Effort Force) was created just to deal with the Mau Mau uprising. This eventually included 14,000 police officers who would go on to arrest up to 160,000 Kenyans. Many of these arrests were made on a ‘hunch’ or weak evidence. Prisoners were interned without trial in concentration camps.

Even in Uganda, the quality of policing in the build up to independence was questionable. British policeman Stewart West would reflect: ‘Overall I was very uncomfortable with the case files constructed, and felt that a lot of old scores were being settled with false evidence.’

When lawyer Milton Obote arrived at a prison, offering to defend those arrested for protesting, he was refused access. ‘I was even more upset’ reflected West, ‘when the magistrate started handing down sentences of two to three years imprisonment for offences that probably deserved a binding over to keep the peace’.

Although colonial law in East Africa had a very high opinion of itself, in practice things were messier. Illegal arrests, unfair sentences, the use of the police to intimidate political opponents, all of these activities were familiar to the colonial state. Unfortunately, when Africans finally seized the reigns of power, their leaders maintained these practices with little modification.

Wind without Change

In Uganda, Tanzania, and Kenya, post-independence policing shared several similarities. Firstly, there was a sense that police were obliged to obey those in authority. If the President requested it, it should be done. Secondly, the police were supported by political militias and village vigilante groups who became responsible for some of their ‘dirty work’. Finally, policing became heavily biased in favour of the ruling party, with loyalists recruited and promoted to the highest ranks.

In Tanzania, the Field Force Unit was a special police branch created by the colonial government targeting pro-independence groups. However, when the country gained independence, the FFU was allowed to continue. In fact, the state started using FFU to crack down on its opponents. Only members of the ruling party were recruited. In the 1970s FFU broke up student protests, killed demonstrating workers, and ended strikes.

Supporting FFU were informal vigilante groups also loyal to the state. Militia groups called ‘Sungusungu’ were officially recognised by the government in 1971, becoming accountable to the local police and being given the power to make arrests.

What was legal and illegal didn’t matter, since orders often came directly from the highest echelons of government. Police simply came to believe this was how their job worked. They rarely felt the guilt Stewart West had over unfair process or arrests. They were doing what the government told them to do, and that’s what policing was all about.

At a meeting held in Dar es Salam in 1976 to determine how a witch hunt got out of control, several police officers testified ‘they knew what was being done was unlawful but were still prepared to do it because orders came from the top’. Policemen working under Idi Amin’s government in Uganda, or Daniel Arap Moi in Kenya, justified their behaviour in the same way.

Abductions are a Mystery

East Africa’s police had a serious cultural and institutional problem. A sickness which normalized abductions and intimidation. Even apparently decent people were sucked into this pattern of power. The well meaning lawyer Milton Obote who had tried to defend his clients during the colonial era, would go on to become Uganda’s president. Obote then appointed his cousin to run a special police force responsible for intimidating and abducting his opponents.

As the rise in abductions grew, the government’s of East Africa looked for somewhere to keep their illegally arrested prisoners. In Kenya, Daniel Arap Moi’s police used the basement of Nyayo House where inmates were subjected to abuse. By avoiding normal prisons, the government was making a statement: the state was above the law.

This feeling that there was a shadowy dark power which could strike anywhere, without accountability, terrified people. It weakened opposition and gave ruling parties unquestioned power. It was the mystery of the African ‘deep state’.

Idi Amin’s regime in Uganda mastered this fearmongering strategy. The explosion of ‘disappearances’ that followed his rise to power were unexplained. In fact the government repeatedly denied all reports of violence and killings, calling these stories lies, even as they were carrying them out. People were confused, scared, and submissive. Unsure of where to turn or what to do.

This was the big attraction of an abduction. It didn’t just remove a political threat. It left the masses whispering and nervous. Without high tech crowd control, mysterious abductions seemed an obvious way to decrease the likelihood of protests. And at their disposal, East African elites had a compliant, compromised police force, and a collection of loyal militia groups. Abductions became the norm.

The Story Continues?

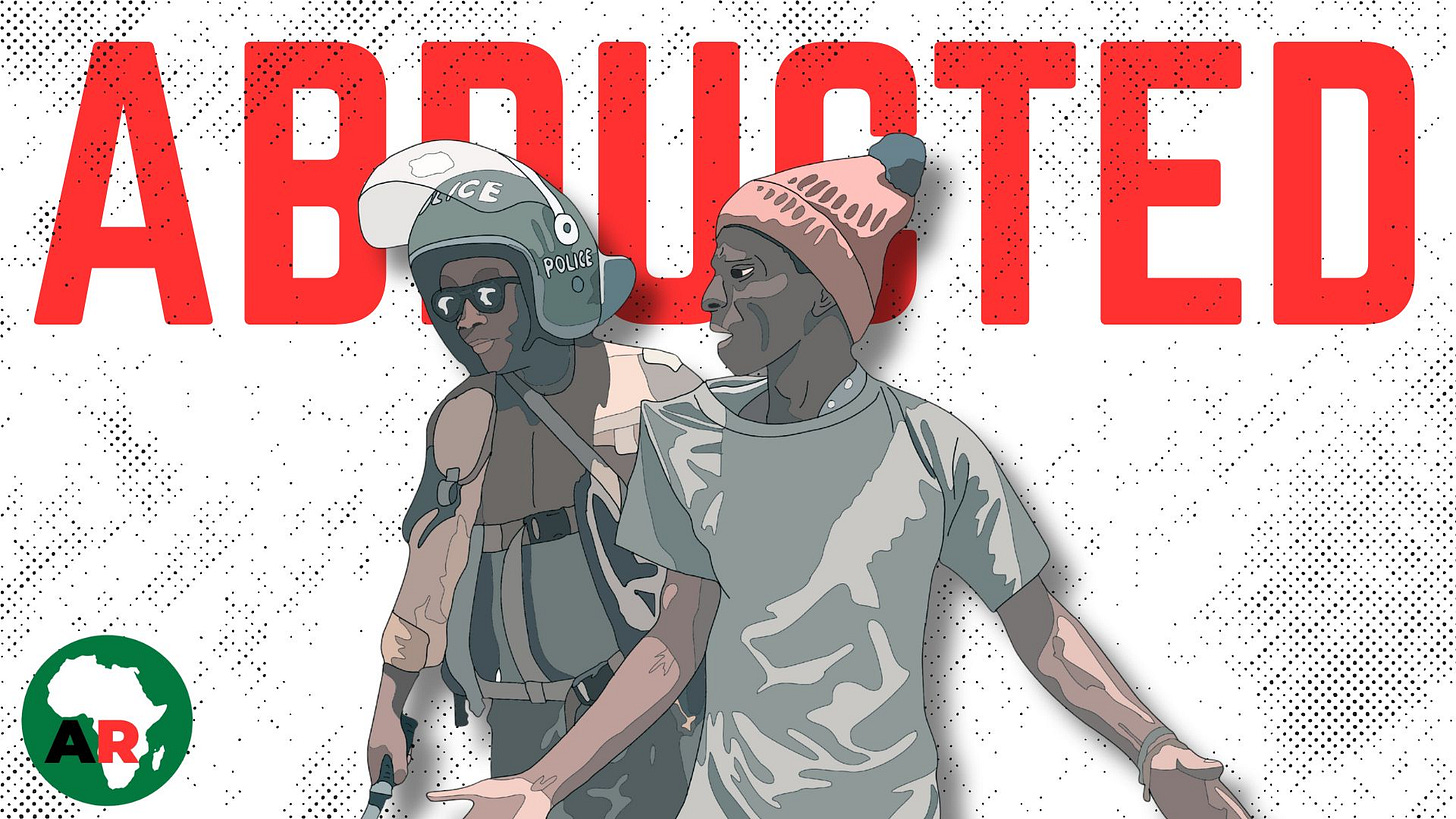

Current East African leaders, Mama Samia, Museveni, and Ruto, all draw on the same playbook of abductions. When Ugandan opposition figure Dr. Kizza Besigye disappeared in Nairobi and then reappeared in a military jail in Uganda, most observers assumed the two governments had done a deal.

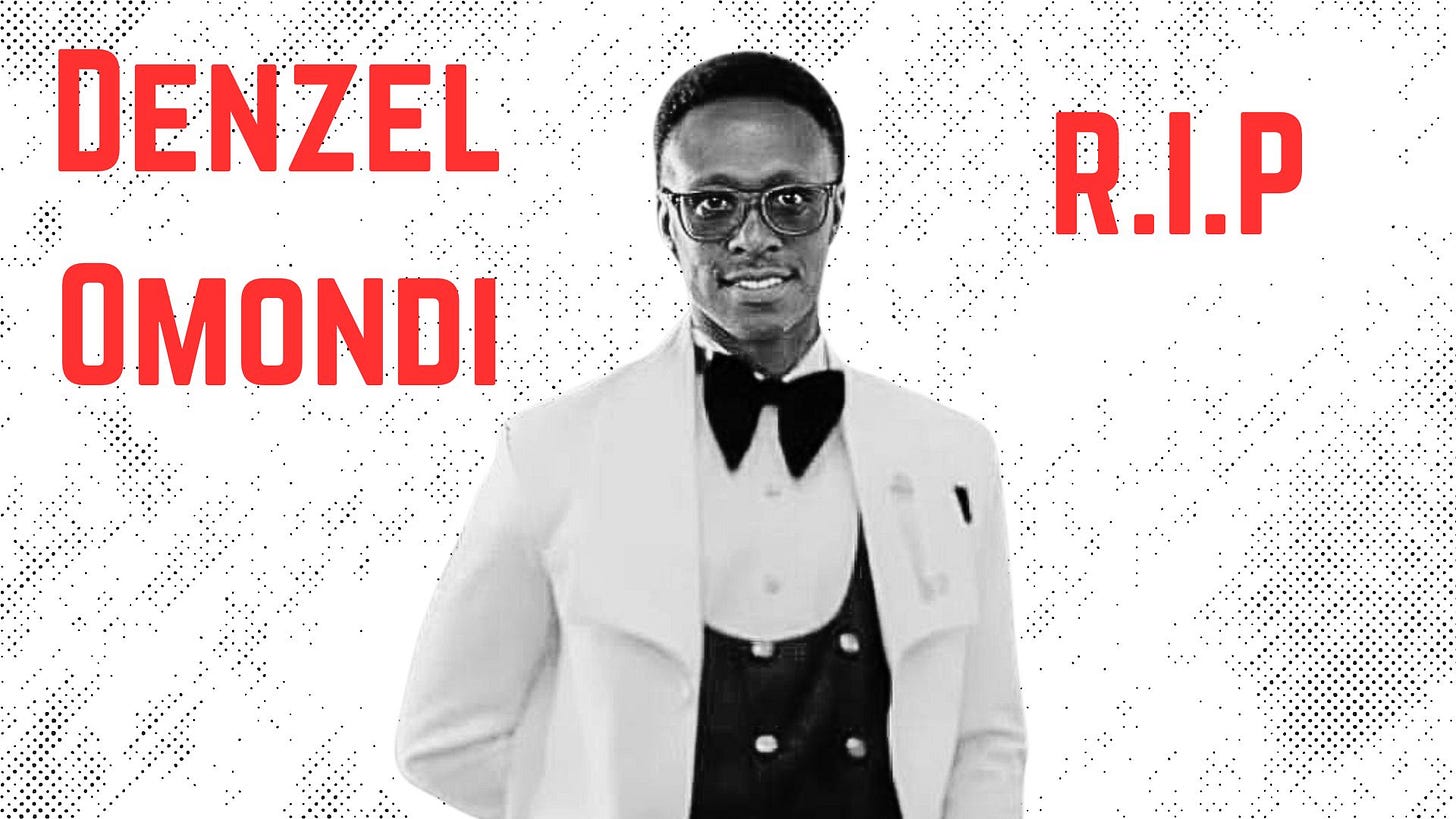

When protesters flooded the streets of Nairobi during the finance bill protests, Ruto deployed abductions as a strategy to spread fear and limit unrest. Some of those who disappeared, for example Denzel Omondi, never returned alive.

Meanwhile Museveni’s son General Muhoozi has publicly boasted on X that he is holding disappeared opposition figures in his basement. Even sharing humiliating photos of them.

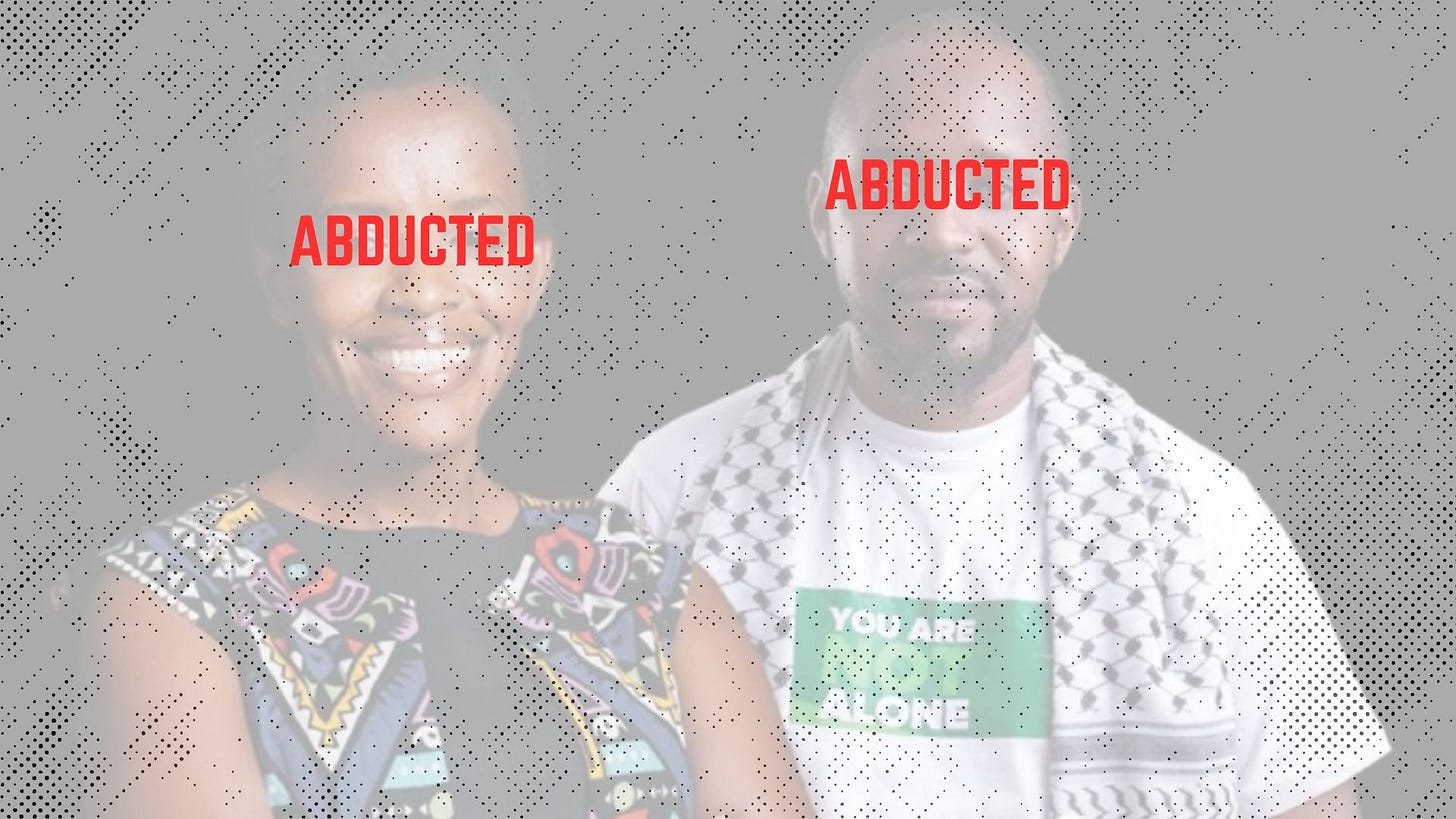

And although Tanzania reports the lowest official figures for abductions, in reality it’s leader Mama Samia may be the worst offender of all. ‘In Uganda, we are being ruled by a dictator, but when I arrived in Tanzania… we were abducted by thugs whilst inside a police station,’ remembered opposition activist Agatha Atuhaire. Her and the Kenyan Boniface Mwangi were subjected to brutal behavior by the Tanzanian police.

When the next day an MP for the ruling party preached against abductions from the pulpit, he found police had arrived to shut down his church. There are no abductions in Tanzania. Or else!

In reality, abductions are an expected part of political life in East Africa. They are so ingrained in the national consciousnesses that hoax abductions are now a thing. Kenyan MP George Koimburi was seized outside his church before being found bleeding in a field the next day. Outrage shifted to confusion when evidence began to emerge Koimburi may have masterminded the whole thing himself for publicity purposes.

The sad truth is there is no need to cry wolf in East Africa. The wolves are already in the fold carrying off the sheep. Koimburi is simply not quite important enough to be targeted. He has already been discredited by false claims he made about MPs salaries.

Uganda, Tanzania, and Kenya all inherited problems with police from the colonial era. These problems festered like a disease as ruling parties used law enforcement to maintain power. Today abductions exist because of these systemic issues: a problem encompassing police academies, informal networks of power, and compromised judicial systems.

Each new leader says to themselves ‘everyone else is doing it so why shouldn’t I?’ Only concerted political pressure can bring abductions to an end. It may be that in Kenya, we are beginning to see the start of just that.

Sources:

https://academic.oup.com/book/39312/chapter/338916188

https://asset.library.wisc.edu/1711.dl/OTRO7BSOLDR279D/R/file-150a6.pdf