The facade

The perfect lawns and neat rows of Port Sunlight, England, are a strange place to start a story about colonialism and greed. Built by the businessman William Lever in the 1880s, Port Sunlight was designed to be a ‘model village’ for workers in his factories. This ‘moral capitalism’ made Lever the darling of Victorian Society. You could become immensely rich and save the world at the same time.

The condescending kindness on display at Port Sunlight convinced Belgian colonial authorities to allow Lever Brothers into the Congo. Unilever’s plantations in Africa became a toxic combination of brutal intimidation and paternalism, mistreating workers whilst telling them it was for their own good.

But the plantations are just one small part of the company’s colonial ventures. Unilever’s subsidiary, the United Africa Company, would expand its operations to 42 countries. In parts of Nigeria, UAC’s monopoly was so extensive it was known as the ‘alternative government’ long after independence.

Colonialism helped create the first modern multinational company, but its impact was not just financial. In the 21st century, Unilever continues to use ‘moral capitalism’ to justify expansion. It continues its efforts to change the private lives of billions of people in the name of the global good. But behind the facade of condescending kindness lies a different reality. This is the story of that reality, the true story of Unilever in Africa.

The quest to be clean

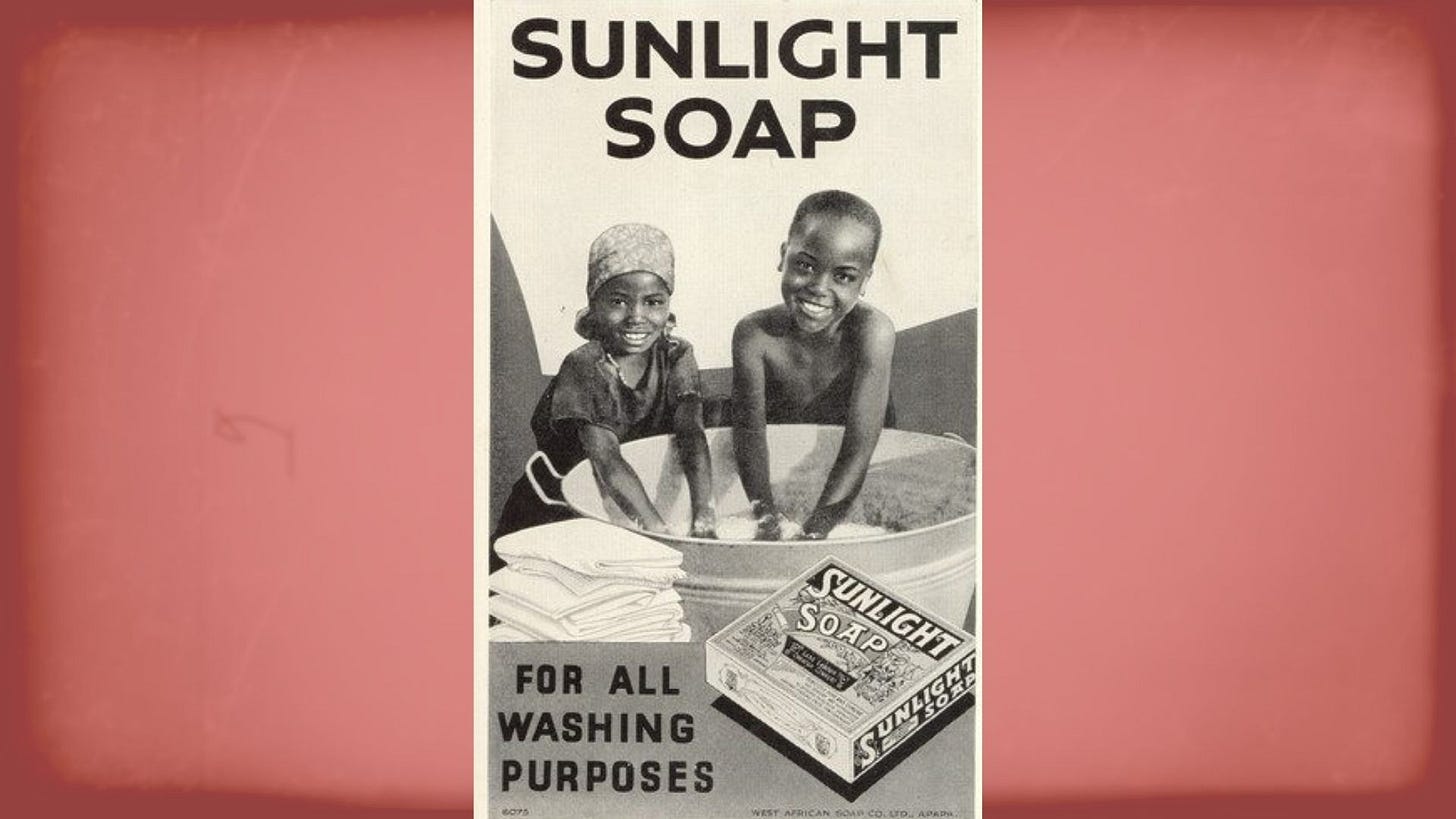

Britain’s large cities were a filthy place in the 1800s. In 1858 London, a heatwave led to an event known as the ‘Great Stink’. Leaking cesspits spread diseases like cholera. Very slowly advancements in science and technology improved the situation. Handwashing was promoted. Germ theory changed the understanding of disease. Demand for cleaning products grew.

In the past animal fats had been used to collect dirt. Soaps were sold in long expensive bars. Using a newly discovered way to make soap out of plant oils, Lever Brothers grocers began making and selling ‘Sunlight’. Sunlight was sold in smaller more affordable packages and didn’t go rancid. The product was so successful it launched a hygiene and nutrition empire. Lever brothers expanded into other areas like margarine.

One of the challenges faced by the business was sourcing plant oils. Something which led Lever Brothers to turn to West Africa.

Colonising Nigeria

From 1910, Lever Brothers began buying small trading concerns in West Africa. (WB McIver & Co, Peter Ratcliffe & Co, the Bathurst Trading Co, John Walkden & Co and Richard & William King). Its largest acquisition was The Niger Company in 1919. Formerly the Royal Niger Company, this organisation had played a crucial part in the British colonization of Nigeria.

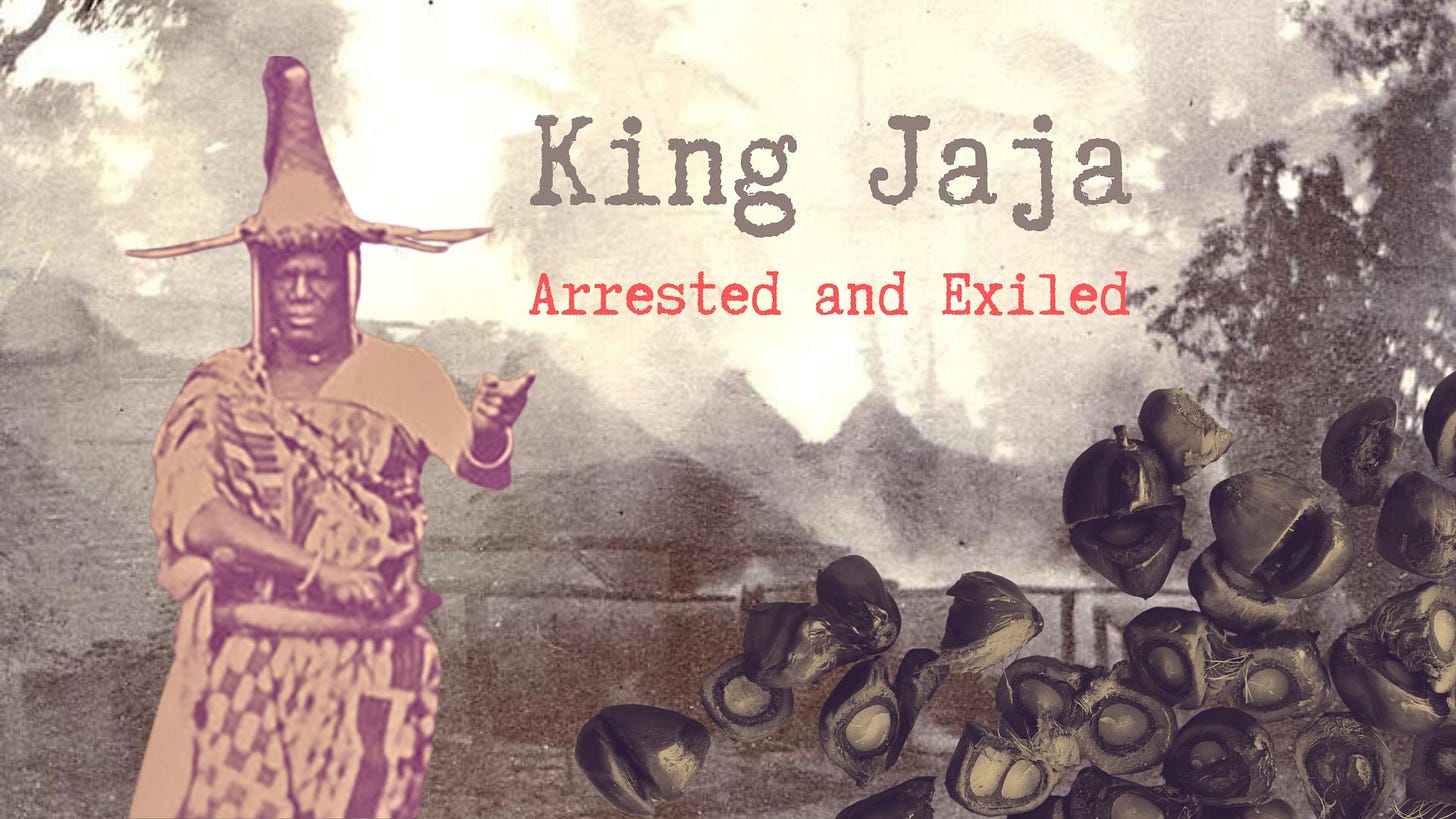

RNC had been exploring and trading in West Africa from the 1870s. In the 1880s the company engaged in a price war with French competitors, eventually establishing a monopoly on the coast of Nigeria and along the Niger river. Over 400 local chiefs were tricked or coerced into signing treaties promising to only trade with the company. Africans like King Jaja of Opobo who tried to establish their own trading companies were arrested and sent into exile.

Eventually RNC’s ruthless behaviour came back to bite it. In 1895 a small war broke out when King Koko of Nembe refused to sign an agreement with RNC that would have given them control of the local palm oil trade. The Royal Navy intervened, destroying the Nembe capital. After the violence, the British government took direct control of the territory, eventually integrating it into the state of Nigeria as we know it today.

When Lever Brother’s acquired the Niger Company 25 years later, they were buying into a legacy of colonial intimidation and coercion. But above all they were buying an organisation focused on monopolising trade. As one Niger Company manager wrote in 1920, ‘The purpose of our business is the purchase of cash, in order to buy produce’.

The Niger Company connected Lever Brother’s production hub in England, to the source of raw resources in Africa, where the palm oil used it into soaps was grown. But the company’s control over its supply chain was still limited. In some areas it remained dependent on African middlemen who bridged the gap between European traders and small-scale farmers. William Lever’s desire to monopolise the soap supply chain led him towards the world of the plantation.

Congo plantations

Lever’s interest in plantations preceded his purchase of the Niger Company. In 1902, Lever Brother’s established coconut plantations in in the Solomon Islands, with the aim of supplying its soap factories in Australia. This would also serve as a test run for its Africa ventures. The plantations were productive, exporting tens of thousands of tons of coconut fat each year. But the managers also came into conflict with local British administrators who took land claimed by local islanders away from the plantation. Similar problems would beset the company’s Africa plantations.

In West Africa, British colonial officials were distrustful of William Lever’s plantations plans. The British Governor was opposed to encouraging a cash crop economy, telling Lever he hoped Nigerians would "not fall into the temptation of producing a crop which is valueless to them unless they can dispose of it for export."

Undeterred Lever looked elsewhere for his African plantation, eventually finding a warmer welcome in the Belgian Congo. The Belgian government had recently seized control of the vast Congo territory. Previously it had existed as a private possession of the Belgian King Leopold II who oversaw a brutal system of resource extraction which left Congo in chaos and polite European society horrified. Lever, with his reputation for ‘moral capitalism’, seemed like the perfect candidate to develop the economic potential of this vast territory.

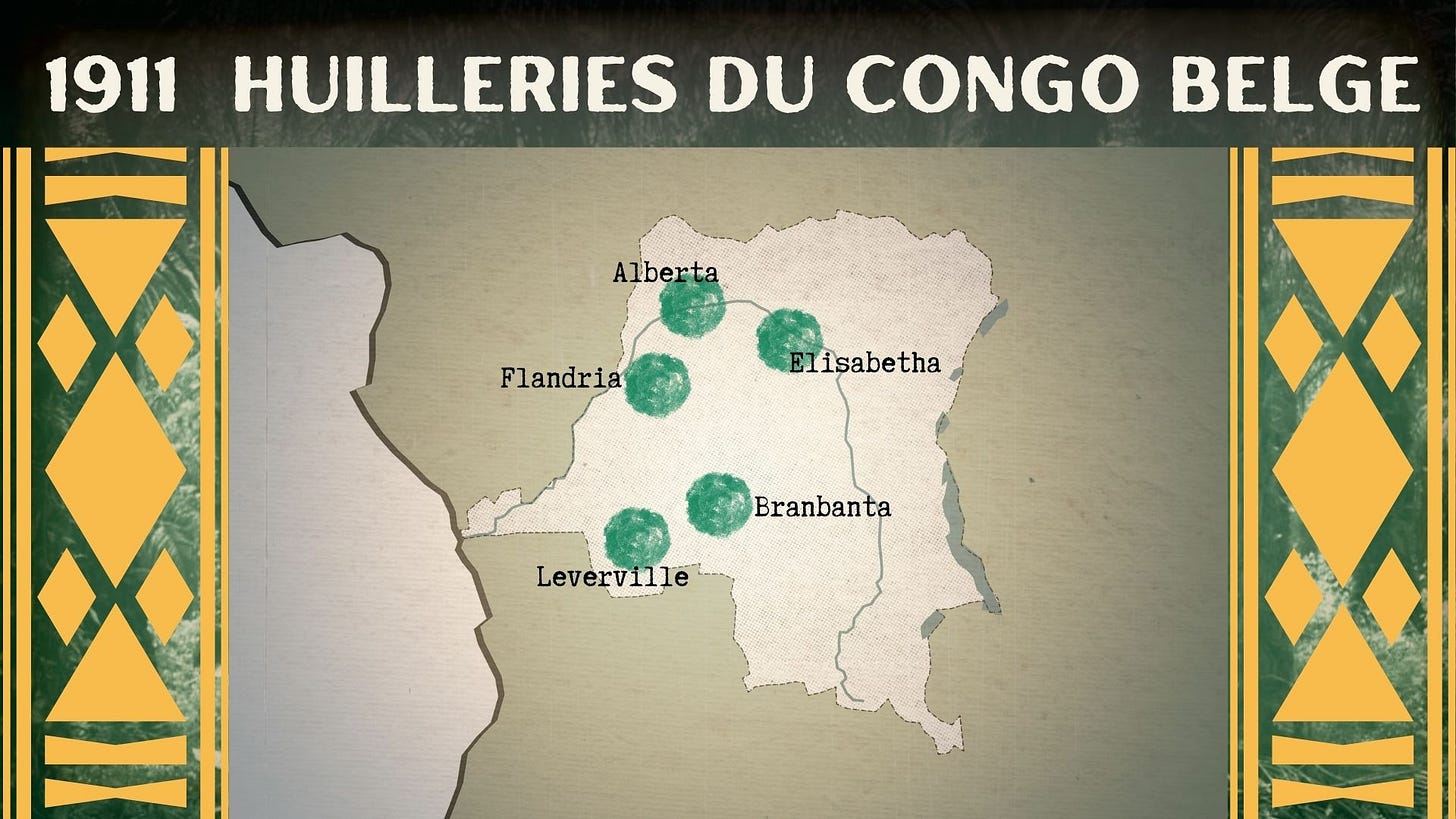

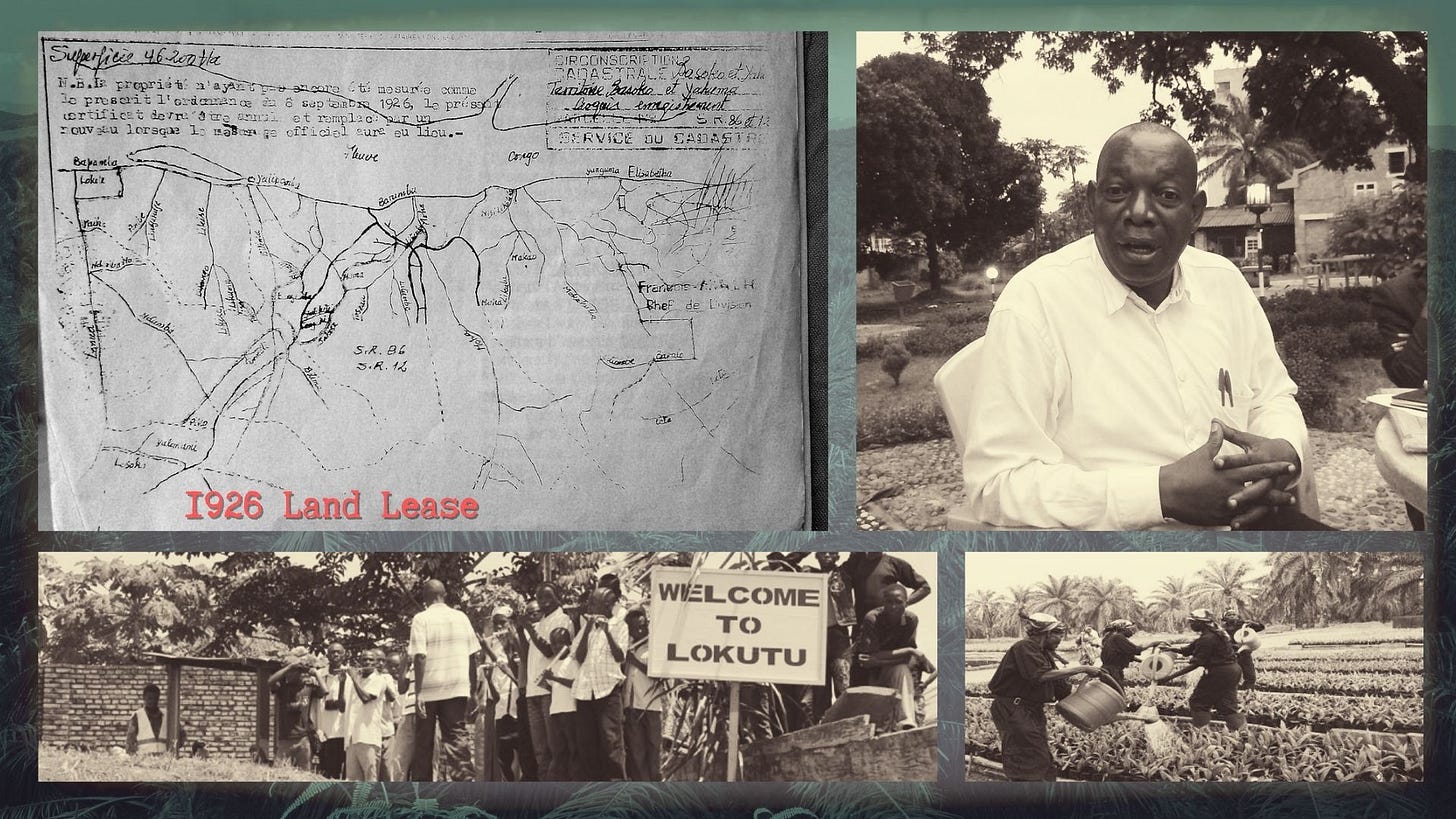

In 1911, Lever Brother’s created the subsidiary ‘Huileries du Congo Belge’ and were granted a monopoly to harvest all palm fruits within 5 circles, with a radius of 60 kilometres. Alberta in Bumba, Elisabetha in Basoko, Brabanta in Basongo, Flandria in Ingende, and the company’s headquarters, Leverville in Lusanga. In total they held a monopoly on palm oil in roughly 57,000 square kilometres. This state within the state was known as ‘Leverland’.

Model villages were built in Leverville to attract Africans to work for the plantation. Hospitals and shops were constructed. Later a soap factory was built opening factory jobs for Congolese. Alongside this development came a condescending attitude and a desire to ‘help’ local people. For William Lever, the Congo plantations were a kind of ‘social work’ like Port Sunlight. He would privately reflect in his diary on his duty to help Africans who were ‘millions of years behind’ Europeans.

Unfortunately, many local people seemed reluctant to work in the plantations. They were distrustful of HCB’s offer of a different way of life and demands on labour. To solve the problem plantation managers used the Belgian governments covert forced labour procedures. Colonial administrators would accompany plantation managers to villages, instructing chiefs to send people to work in Leverland.

Within the model villages workers were subjected to disturbing levels of control, designed to make them dependent on HCB hospitals and shops, whilst they learnt cash cropping skills of limited use beyond the plantations. Many European managers resorted to brutal behaviour to punish their workers. When confronted by these issues, Lever Brother’s head office invariably supported the managers, arguing it was the impact of a hot climate.

William Levers paternalistic racism allowed him to argue he was helping Africans, but the company’s economic motivation was to control the price of palm oil. Fluctuation in palm oil prices were affected by weather and the dynamics between small-scale farmers and African middlemen. The plantation model ensured Lever Brothers could effectively exploit the African producers at the start of its international supply chain.

The legacy of Lever Brother’s abusive and disempowering plantations remains in the Congo today. In the 2000s Unilever sold its holdings to the Congolese multinational Feronia but the model of agro-colonialism continues. Local people have been forced into total dependence on the plantation as a source of income. Privately grown food crops are destroyed by plantation managers who see them as a threat to the plantation’s economic monopoly. If a worker disappears, their families flee fearing intimidation to keep them quiet. Meanwhile, activists argue the plantation’s land was illegally granted by the Belgian government and should now be returned to local people. William Lever’s legacy of is painful and enduring, but it stretches far beyond the Congo.

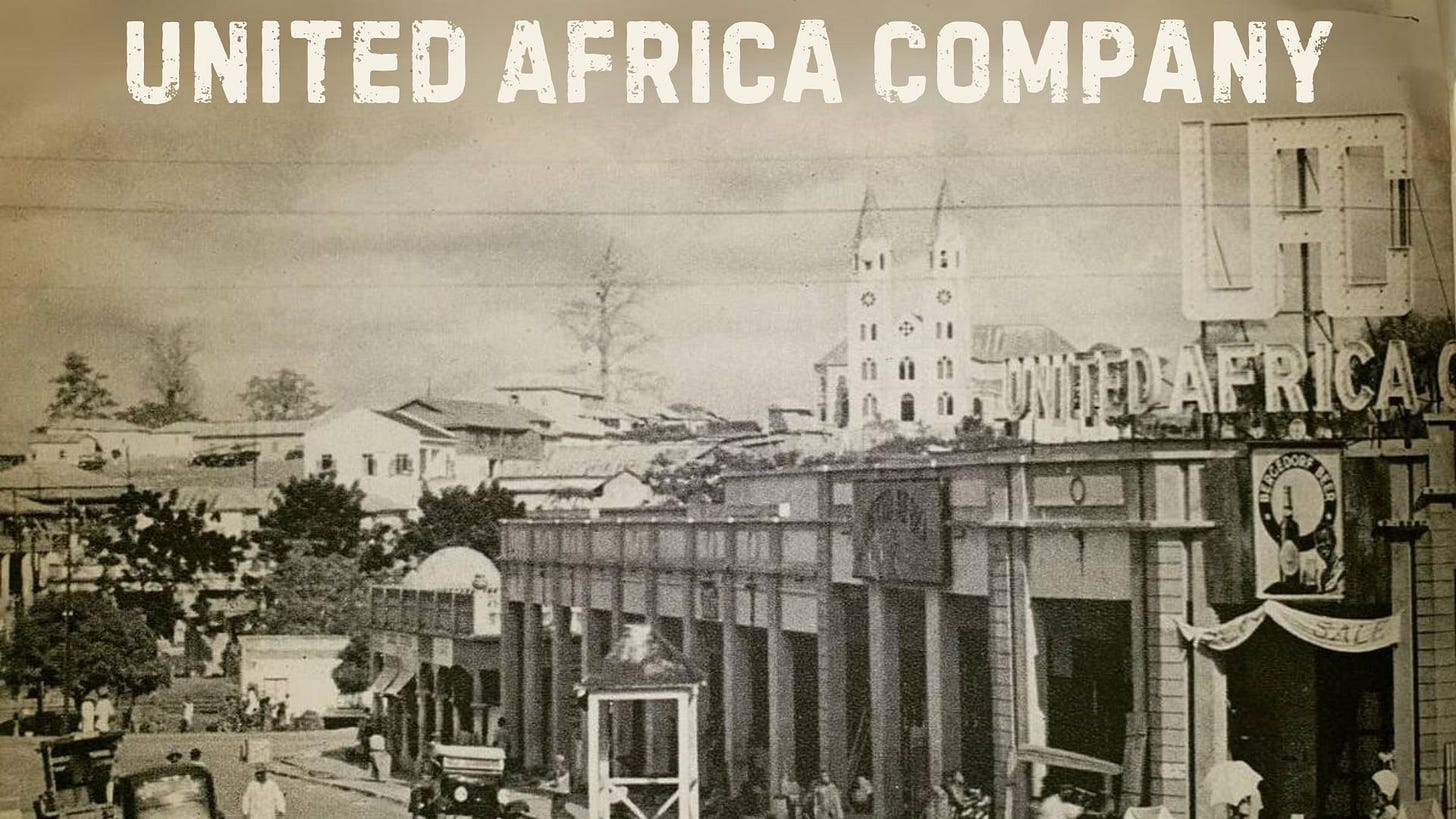

United Africa Company

Lever Brothers and the Dutch margarine union joined forced in 1929, creating the company Unilever. At the same time in Africa several European trading companies joined together, including the Niger Company. This amalgamation was called the United Africa Company and by 1930 the UAC had become a subsidiary of Unilever. But UAC had a lot of freedom. It only reported its accounts annually to the Unilever board. Over the next 30 years UAC would become a multinational giant, with operations across Africa and the Middle East.

UAC acquired palm oil plantations in Cameroon, Sierra Leon, and Nigeria (Pamol) but much of its produce came through small-scale farmers. To better control the prices UAC organized groups of commodity buyers with companies like Cadburys, protecting their profits and forcing prices down.

For African farmers middlemen created competition for their produce, giving them some leverage on price. UAC viewed the African middlemen traders as a disruptive force in the market. UAC pressured the colonial government into creating state-controlled marketing boards which fixed prices and established monopolies for favoured companies. In this new set-up UAC became the controlling force in the market for produce buying, a change coming at the expense of many African traders.

UAC quickly expanded into other areas including timber extraction and car and petrol sales. UAC promoted West African hardwood as conveying a ‘feeling of warmth’. As African forests were cut down, British offices filled with ‘warm’ wooden furniture.

In many markets UAC worked closely with the colonial government. The logging activities aligned with the British governments drive to promote ‘Empire timber’. In the 1940s a UAC director suggested a largescale groundnut oil scheme to transform Britain’s East African colonies. The Tanganyika Groundnut Scheme was a famous economic disaster which came at the expense of the British taxpayer. UAC seemed to be much more successful in its own self-funded ventures.

By the 1960s the company has investments in breweries, consumer goods manufacturing and distributions, medical equipment and pharmaceuticals, advertising consultancy, office equipment, construction tools, insurance companies, building materials, food and textile production and, of course, a shipping line. UAC in Nigeria was an importer, exporter, manufacturer, and retailer, dominating all aspects of the market and popularly referred to as the ‘alternative government’. One Nigerian Professor would despite it as ‘a formidable foreign social system within the Nigerian economy.’

UAC survived African independence for several reasons. Firstly, it had begun to fund charitable activities and sports events in Africa, giving it a positive image. Within the company, funds were invested in training the African workforce, a select few were being groomed for senior management. In its marketing UAC portrayed itself as proudly Africa. But perhaps the biggest reason UAC continued operating across Africa was it was simply too big to fail. Breaking it apart threatened economic chaos. In Nigeria and Ghana UAC was the largest private sector employer.

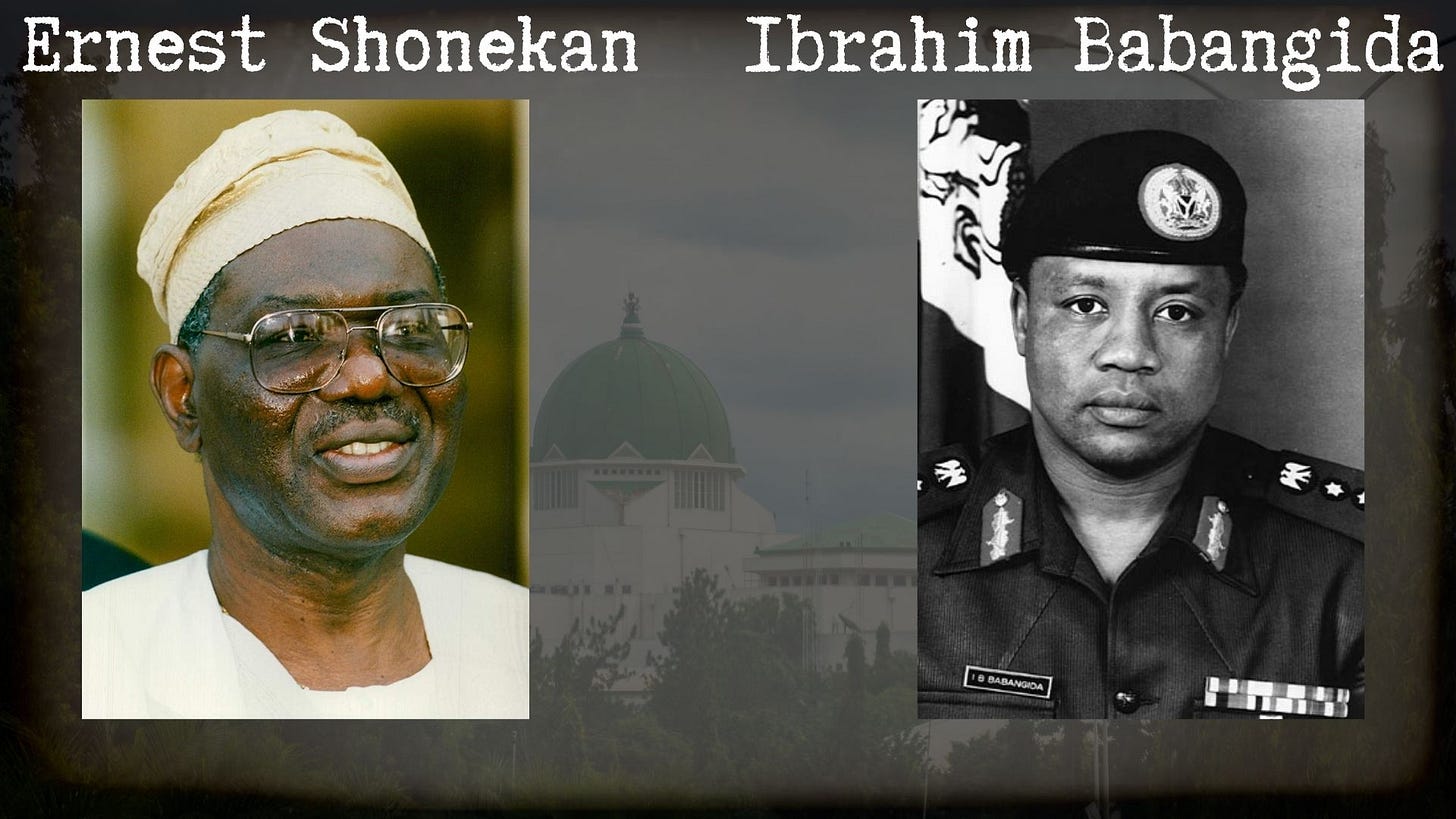

In any case African governments were usually more than happy to replace the colonial government as state beneficiaries of UAC’s monopolies. In UAC Nigeria Ernest Shonekan was appointed as director and chairman. He was well known for his close connection to President Babangida. Shonekan would gone on to become president of Nigeria himself.

UAC was eventually broken up in 1987 when a large part of the organisation was absorbed into Unilever’s Africa and Middle East operations. Other parts of the company continued operating in their respective countries. UAC Nigeria is well known today for its fried chicken franchise. To the last UAC boasted a higher profit margin percentage than any other area of Unilever’s operations. After the restructure, it wasn’t long before Unilever turned its attention to Africa again.

Unilever in Africa Today

In 1984 Unilever acquired PG Tips and Lipton expanding its African estates holdings. In many places the conditions endured by tea workers were not dissimilar to plantation life. By 2020 stories of coercion and abuse on PG Tips plantations in Kenya had made the brand a publicity nightmare for Unilever. A year later the company sold all its tea holdings.

Lever Brothers had always justified its aggressive capitalism in moral terms, and Unilever began doing the same thing. Improved factory efficiency was driven by a profit motive but presented as environmental altruism. Selling its plantations and estates, Unilever presented itself as an ethically minded buyer, working towards sustainable sourcing of palm oil. This image of corporate moralism was accompanied by a new strategy in Africa.

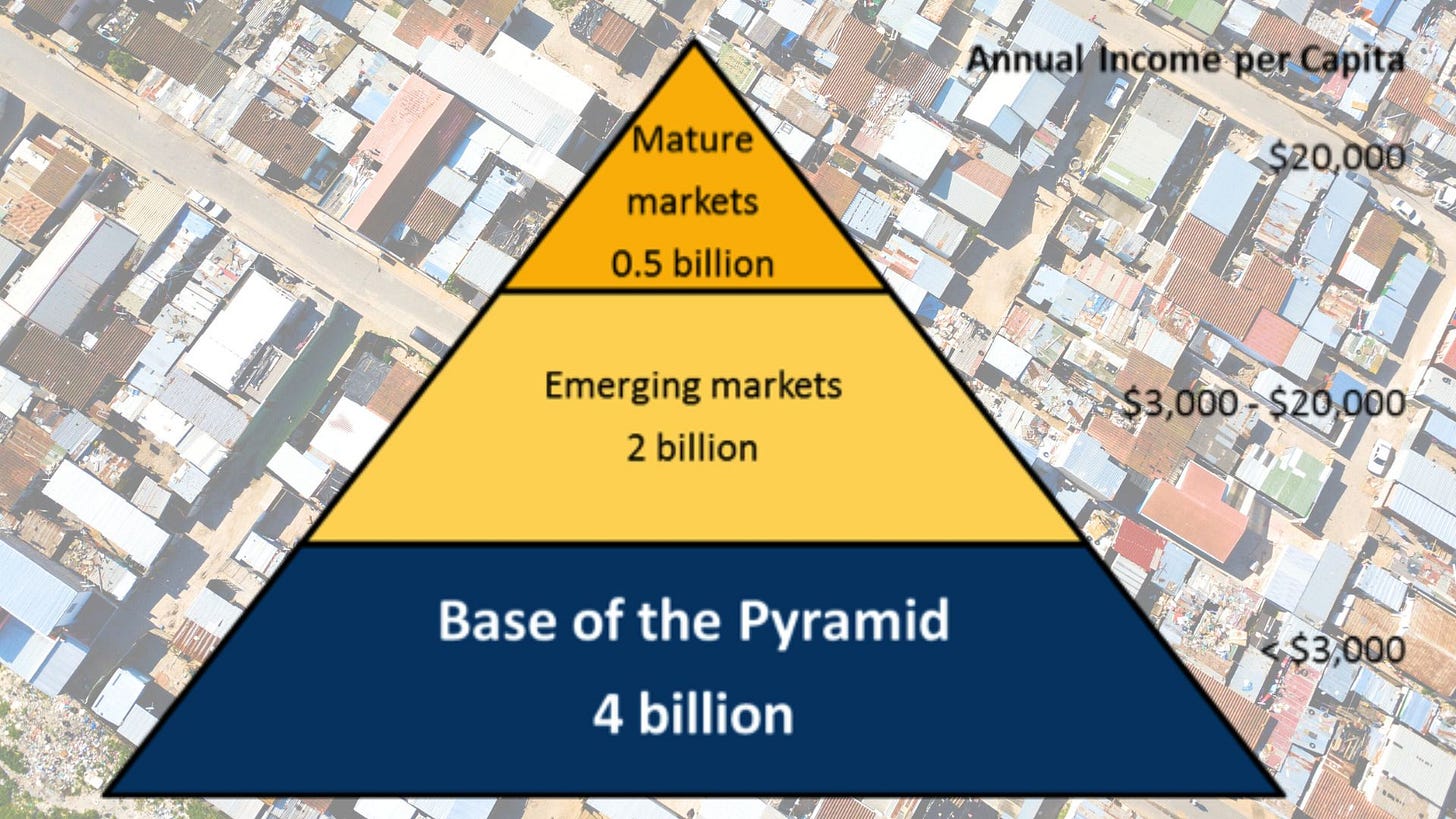

Lever Brothers’ original success came from providing an aspirational product to people with less expendable income. You can make a lot of money from poor people, especially poor people with aspirations. By 2011 Unilever was changing its global perspective on Africa. ‘The future of Africa is based around a consumer rather than mining’.

Unilever is especially interested in what it calls Bottom of the Pyramid consumers. Africans who aspire to have scented laundry and clean homes despite living in slums like Kibera. Many of these BOP consumers struggle to afford large quantities of Unilever products which is why it has introduced smaller packaging. Consumers with less expendable income cane still by some Omo or Lifebuoy, even if they cannot afford a whole bar.

The company has presented this move to small packets as a social good, helping Africans access hygiene products. Of course, small packages equate to higher profit margins and a worse overall deal for consumers. The price per gram is much higher in smaller quantities. In a sense, Unilever is taking advantage of BOP consumer poverty to increase spending on its products.

This aggressive drive into the BOP market has been accompanied by strategies to expand and grow the bottom of the pyramid. In some rural areas personal hygiene products are seen to be less of a priority. Unilever has invested hundreds of millions of dollars into sanitation and hygiene projects in Africa. Many of these projects have been completed in partnership with governments and NGOs like UNICEF.

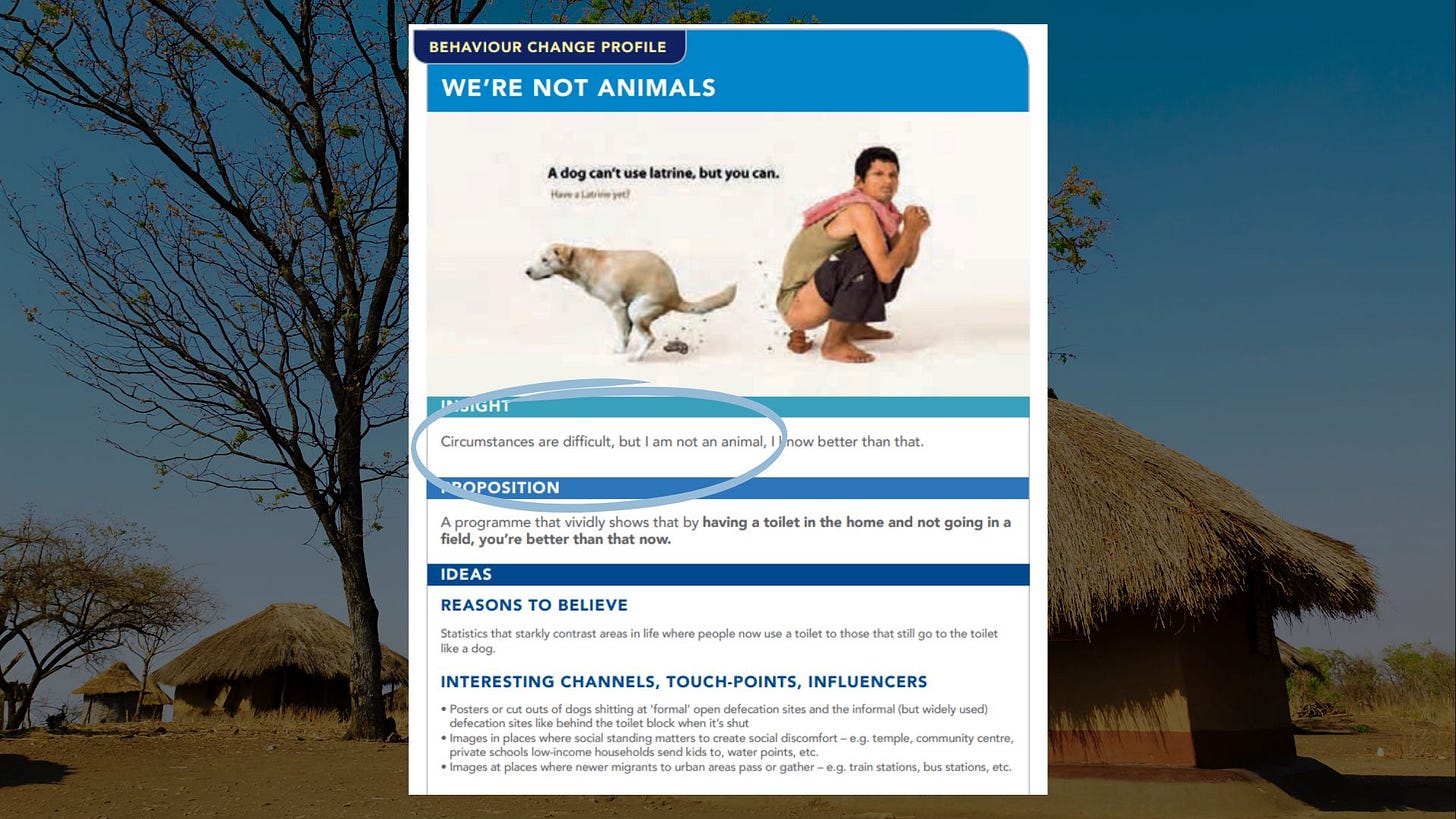

But Unilever is not very interested in actual infrastructure provision. It rarely funds projects constructing municipal sewage systems. Rather, it is attracted by a brand of social engineering known as Community Led Total Sanitation. The Company’s enthusiasm for CLTS led it to create a free guidebook now available online. Unilever promotes a brand of CLTS which actively encourages shaming and emotionally blackmailing poor communities into spending their limited income on home latrines and sanitation products.

In the 1920s Lever Brothers placed itself at the forefront of personal hygiene campaigns in Britain. School children were encouraged to record their handwashing habits. During World War II, residents of London who didn’t have access to water were offered warm showers by Unilever. In these situations, the organisation was careful to respect the dignity of people whose private lives they were invading.

In modern Africa no such qualms exist. CLTS aims to whip vulnerable communities into an emotional frenzy of guilt and anxiety. Aid workers are encouraged to tell ghost stories to frighten Africans from going to the toilet at night. Drawing on colonial stereotypes, people who defecate outside are compared to animals. Children are encouraged to write letters to their parents asking they follow the advice of NGOs. Fake deworming medication is offered, the package containing instructions on how build a home latrine.

Unilever’s priorities shape the projects its funding is used on. A grant for building a municipal sewage system in Kibera slum would transform the neighbourhood but be of little benefit to the company. From Unilever’s perspective, funding the creation of anxiety over personal hygiene funnels Africa’s poorest directly into its BOP consumer target group. And whilst profiting from this manipulative and condescending behaviour, Unilever can proudly tell the world ‘it’s for their own good’.

Behind the facade

By presenting its for-profit activities as charitable work, Unilever has disguised its aggressive market behaviour as ‘moral capitalism’. Whether cleaning the unwashed masses of Victorian Britain or selling small packets of Omo in modern African slums, Unilever has displayed a disturbing desire to control the most private parts of people’s lives.

In reality, the company has looked to create dependency on its own products and systems. Victims of this disempowerment can be found in the struggling indigenous soap industry in West Africa, which existed in pre-colonial times, and in the plantation workers in Feronia who have been trapped for generations now in a system which exploits their labour and denies them agency.

The organisation’s interest in monopolising the supply chain drew it into plantation ownership in Africa, but today Unilever has managed to decouple itself from most of these sources of negative publicity. And as it preaches responsible sourcing at international forums, it is happy to quietly buy raw resources from companies like Wilmar and Olam, notable for their abuse of workers rights and deforestation.

So perhaps for Africa, the most dangerous aspect of this multinational remains its facade, its long history of justifying controlling behaviour as a social good. Unilever was not just a product of colonialism; it continues to replicate a colonial culture of exploitation and self-justification.

Sharp as a quill and twice as precise…your words cut through noise with wit, relevance, and most importantly unapologetic truth.

Always a joy to read, Thank you for holding the mirror up while others look away!

Really appreciated this article! Growing up in Addis Ababa, I remember Omo very clearly as our go-to product--not surprised that, as many things in Africa, it has a legacy (and sill is) of colonial exploitation