Would you like to support high quality African journalism? Why not join The Africa Review’s paid members and receive an exclusive article each month.

Plus, your contribution will help us keep creating articles for everyone. It's a win-win! You can join using this link:

What actually matters?

Bill Gates loves Africa. But do Africans love Bill Gates? If you listen to the continent’s political elites, the answer is probably: yes! Gates recently received awards from Nigerian and Ethiopian presidents. Graca Machel, a stateswoman in her own right and Nelson Mandela’s widow, has welcomed his support.

But these friendly noises are mostly surface level. A quick google or gossip in a township bar reveal that if Africans know anything about Bill Gates, it's not necessarily positive. Conspiracy theories abound, especially those connected to healthcare and agriculture, two areas of African society Bill Gates has made dramatic interventions in.

Some of these theories are ostensibly false, but others are more a question of interpretation. Why is he so interested in a continent he has little to no direct experience of? In the absence of a clear answer, memories of destructive colonial development projects have resurfaced. Forced vaccination campaigns in West Africa using experimental treatments. Disastrous agricultural projects in East Africa which delivered nothing but chaos and confusion.

What’s so strange is how little Bill Gates seems to care about these negative rumours tarnishing his presence on the continent. Much of the money he invests in his image goes to European and American media companies. In 2021, it emerged his charity had given $319 million dollars to fund media projects. Of this total, roughly $20 million went directly to African organizations.

Admittedly, some of the other projects affected Africa indirectly, for example grants to journalism training centres. However, the vast majority of funding went to sources most viewed by… well… the reasonably well-off. Affluent Western audiences who tune into CNN ($4 million) and NPR ($25 million), or read The Guardian ($13 million) and Der Spiegel ($5.5 million). All those softly lit interviews with Gates on the BBC ($57 million donated including to BBC Media Action) didn’t materialize from nothing.

Gates’ media ambitions have even reached Youtube, where the German channel Kurzgesagt often uses articles published by the Gates Foundation to support its videos. The Kurzgesagt Youtube Channel received over $500,000 from Gates’ charity (more than was donated to South Africa’s Mail & Guardian, or Nigeria’s Business Daily, both major national newspapers).

In short, Gates has mostly confined himself to influencing ‘key stakeholders’ in Africa: newspaper reading politicians and business leaders. Popular gossip on the continent is just not that important to him. In the West it's a different story, with a lot more money invested in a range of platforms. Perhaps this disparity reveals something. Something about why Bill Gates loves Africa so much…

Everything begins with Politics

Apart from supply chains, very little connected Bill Gates to Africa early in his career. His focus was on computers and the growing Microsoft empire. What set Gates apart were two things: firstly, a ruthless streak which meant he was willing to out muscle, out promise, and eventually buy out smaller competitors. Secondly, he had a brilliant ability to think in terms of networks and loops. Every acquisition and expansion solidified the world's dependence on Microsoft. As one commentator put it in 1987, Microsoft "owned all the bats and the field".

This immense success eventually led Gates to take some time off and go on vacation to ‘Africa’ in 1993 (he does not specify the country). It was apparently there that he had his conversion experience, realising how much worse off many African children were. However, photos from this trip mainly appear to show himself and his fiancee Melinda sitting in the back of a Safari 4x4. Apparently, Gates returned to America and did some more reading and eventually started his charity. Or so the story goes…

Behind the safari conversion experience lies another reality. Gates was simply far too successful at creating interdependent systems. By 1990 the US government was already considering taking Microsoft to court over charges of creating a monopoly. After reaching a settlement in 1994, the issues resurfaced in 1998 and Microsoft found itself in the dock.

Gates made things as difficult as possible for the court during his testimony, arguing over the definition of words like "concerned", "ask", and "we". Eventually the judge burst out laughing at his refusal to commit to anything. Microsoft submitted falsified evidence and purposefully misunderstood recommendations made by the court. By 2000, Gates was considering leaving Microsoft if the company was forcibly split up.

But he didn’t only have legal battles to fight. The court case was big news making headlines around the world. Microsoft took out full-page adverts in the American newspapers, claiming it was being persecuted for its drive to ‘innovate’. It released public letters to the President and hired think tanks to boost its image.

Initially the company was found guilty of creating a monopoly and ordered to be broken up, with Judge Jackson later remarking: ‘Microsoft is a company with an institutional disdain for both the truth and for rules of law’. However, a Supreme Court retrial found Jackson’s comments to news media during the trial undermined the final judgement. By 2001 the government and Microsoft began negotiations for a settlement which would allow the company to remain whole.

Gates seized victory from the jaws of defeat. It was in the middle of this crisis that he chose to create the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, merging two smaller charitable trusts (the William H. Gates Foundation, and Gates Learning Foundation), into a single media-savvy soundbite.

The transformation of Bill Gates' image in the press was extraordinary. By 2005 he and his wife were voted Time’s People of the Year for their charitable work. Gates was not a ruthless monopolist but a kindly, and benevolent genius. Few bothered to dig behind the image and ask what the world’s largest charitable trust actually did.

What is the Gates Foundation?

The Gates Foundation (formerly Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation) uses money earned from investments to fund its grants and activities. Its ambitions were clear from the start. In 2005 it started construction of its headquarters, a two-building $500 million dollar project with a living roof and solar arrays. As more and more money was poured into the foundation by Gates and his friends it acquired shares worth $42 billion. Because it is a charitable trust, it doesn’t pay tax on these earnings.

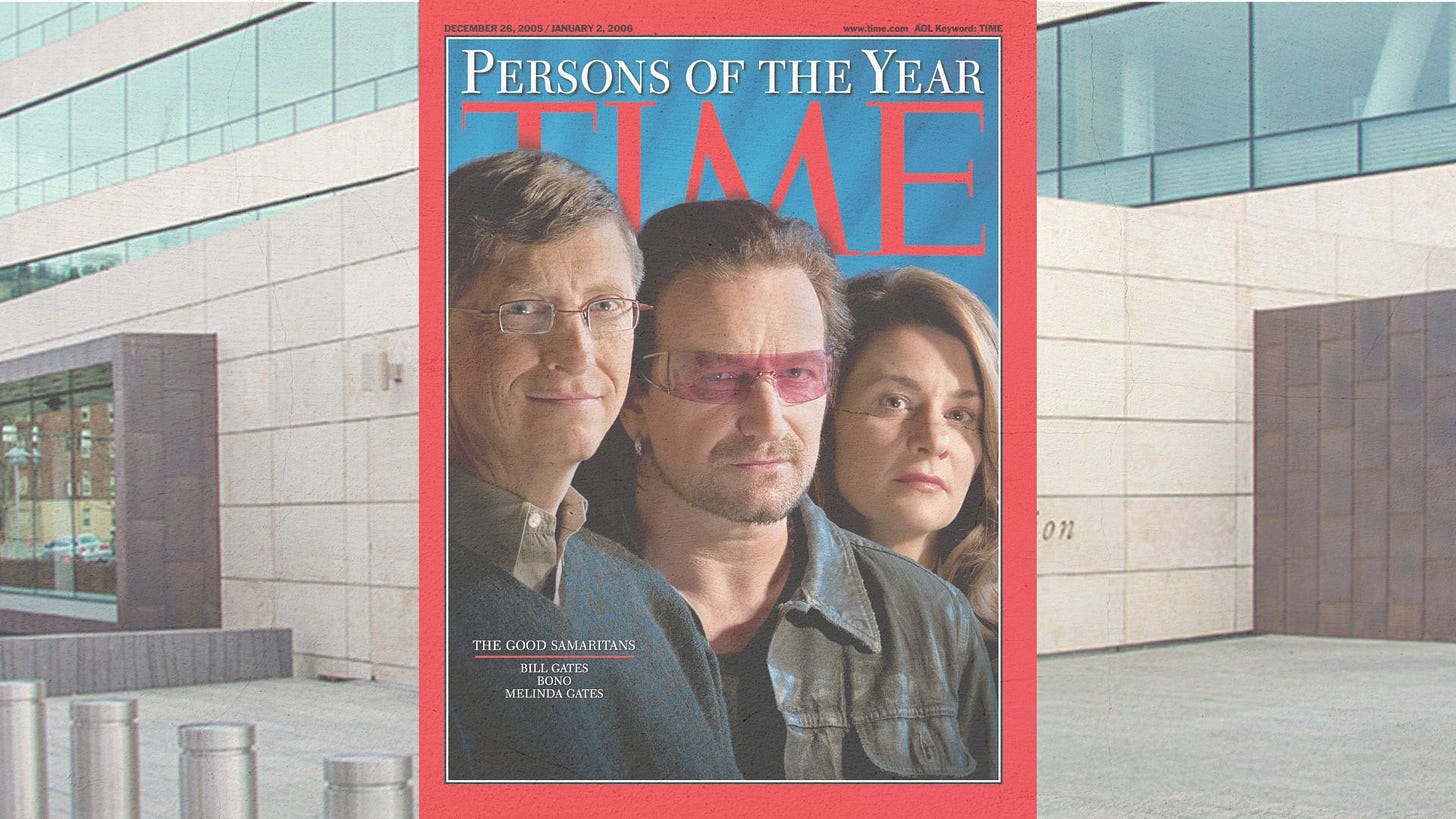

There is some controversy over the charity’s investments. It sometimes invests in companies creating problems for the people it says it wants to help. In Durban, South Africa, for example, it has led cutting edge research on sanitation whilst profiting from shares in oil-refineries that spread pollution in the same area.

Shares in companies like McDonalds, or the GEO group, who run US prisons, seem somehow at odds with the utopian vision of the charity. Despite repeated reviews of its investments, the Gates Foundation has stuck to its guns, arguing investing for maximum profit allows it to have the biggest impact.

Perhaps this kind of argument would make sense for someone who approaches life in a compartmentalized way. Thinking about separate boxes. But this is not Bill Gates at all. His ability to visualise networks and connections is what made Microsoft so successful and controversial.

The truth is Gates’ charity operates in a very similar way to Microsoft. It's just not prioritizing the well-being of Africans when it thinks about its shares. Because as much as Bill Gates is a philanthropist, he is first and foremost a businessman. And he runs his charity, like a business.

The Healthcare Loop

The first network that interested Gates was in the health sector. More specifically, the vaccine industry. In 2002, the foundation purchased stocks in pharmaceutical companies Johnson & Johnson, Merck, and Pfizer. It then proceeded to donate profits from these investments to GAVI, an organisation which promotes the use and distribution of vaccines. To date GAVI remains one of the foundation's largest grantees, receiving $5.8 billion dollars over the past two decades.

This was a characteristic ‘Gatesian’ loop. Profits from vaccine companies are distributed to vaccine promoting organizations, who then grow the market for these companies, who then make more profit, and so on.

Gates was especially interested in finding a vaccine for malaria. With little to no understanding of life in Africa, he approached things from the most basic angle. More lives saved equals a good thing. From 2003 research into malaria vaccines was heavily subsidized by the charity which eventually collaborated with GlaxoSmithKline, linked to Pfizer through the company Haleon (another neat connection).

By 2020, after multiple failures, one candidate vaccine reached stage three trials. It showed roughly 40% efficacy in children although there were some concerns. Participants in the trials had higher risk of meningitis, higher rates of cerebral malaria (a much more dangerous variant), and a doubled female mortality rate. Nevertheless, the pressure to move towards the next stage was intense. If successful, the vaccine could save tens of thousands of lives.

What happened next surprised many healthcare professionals. The World Health Organization launched pilot studies in several African countries but failed to inform parents about the experimental nature of the vaccine. An investigation by the British Medical Journal found that the WHO had failed to inform national medical bodies about the increased mortality rate in girls, and that clinics had distributed the vaccine as part of ordinary vaccine drives. In short, African children had been injected with something they were misled about. There was no informed consent.

Professor Charles Weijer would later remark: ‘It looks like colonial science to me.’ In the 1900s, people like Robert Koch forcibly injected East Africans with Atoxyl, a proposed vaccine for Sleeping Sickness previously only tested on animals. The side effects were severe and the drug did not work.

So how did the WHO get it so wrong that it ended up being compared to racist scientists? Why was there a serious breach of ethics? It's hard to say how the thousands of people who planned, reviewed, and implemented the vaccine pilot study failed to realise something was wrong. However, Bill Gates is widely known to be the WHO’s largest private donor.

The situation seemed to have Gates’ fingerprints all over it. His charity was at the centre of a network he had created over 20 years. A network connecting pharmaceutical companies, vaccine distribution organizations, and the WHO. The people left out of the loop were the very people he claimed to be trying to help. Children in rural African villages.

This is not the first time that the Gates Foundation was caught up in vaccine controversy. In 2010 it funded the distribution of a new HPV vaccine for children in India, again working with GlaxoSmithKline. The vaccine was stopped after seven girls died, and the Indian government launched an investigation. PATH (another US healthcare charity funded by the Gates Foundation) rejected the government’s claims that the deaths were linked to the vaccine. However, the investigation panel went on to conclude that the ‘safety and rights of children were highly compromised and violated’. Some lawyers wondered whether the Gates Foundation was actually complicit in ‘human rights abuses’ through its pressure to implement vaccines before they had been sufficiently tested.

Research and development in the US tech industry has a strong culture of ‘fake it till you make it’. Apple's new AI doesn’t still doesn’t do what was promised. But when tech entrepreneurs enter the healthcare arena problems quickly emerge. Elizabeth Holmes effectively faked her blood testing machine, jeopardizing patient lives and landing her in jail. Medical ethics is at odds with this entrepreneurial culture of grandiose promises and rushed distribution.

Add to this Bill Gates tendency to create networks of benefit and dependency, and the whispers around his behaviour in Africa begin to make sense. When in 2020 the Gates Foundation announced it was planning to partner with Mastercard and GAVI to create a Mastercard ‘Wellness Pass’ there was understandable concern. The plan is to integrate vaccine records with cashless payment capabilities. Wellness Pass is now present in Mauritania and Ethiopia.

It doesn’t mean you can’t buy things if you’re not vaccinated. But in the wrong hands it could potentially be used that way in the future. The pass also ties government services to a foreign multinational. Implementing such a scheme in the US would be massively controversial, but rural Mauritania lacks a global voice or representation.

None of this is a direct criticism of vaccines which save millions of lives. They have certainly made the world a better place. However, the global culture around their development and distribution must be protected. And Bill Gates has a disproportionate impact on that culture. The effects of this aren’t always positive.

Gates understands research and development from a computing perspective. He is a brilliant networker and can create ‘loops’ that benefit his charity and grow its influence. However, he has not trained in healthcare. He has never studied medical ethics. And frankly, his understanding of Africa’s challenges is superficial at best. His disproportionate influence arguably manifests in unethical trials and systems which leave Africans even more dependent on external actors.

There is something wonderfully absurd about Bill Gates' power over African healthcare. In June 2025 Punch newspaper (Gates-funded media in Nigeria) reported that the billionaire was concerned about the small size of the country’s health budget. Gates then went on to highlight the plight of pregnant women who he encouraged not to give birth at home because of the added risks. Hopefully the women in Kano state were tuned in to receive that medical advice from Bill Gates, a man with no experience of obstetrics in developing Africa.

In the same speech Gates then shifted his tone from medical doctor to entrepreneur. There are some very promising trials, he said. Trials that were stopped because they were too successful! And ‘innovation’ is on its way. Lots of healthcare innovation. ‘Innovation’, of course, was the word he used in 2000 to defend Microsoft’s monopoly.

The Agriculture Loop

The Gates Foundation’s second big area of focus in Africa is agriculture. Although not his first love, Gates’ interest in farming has grown over the past decade. By 2018 he had acquired over 250,000 acres of farmland in America, making him the country's largest private landowner. Meanwhile, since 2006 the Gates Foundation has been funding interventions in African agriculture. The plan is to replicate India’s success: a process known as the Green Revolution.

During India’s Green Revolution, which started in the late 1960s, food production increased significantly. Peasant farmers were encouraged to buy new seeds with better yields, sometimes genetically modified. Artificial fertilizers and pesticides were promoted.

In provinces with fertile soil and high rainfall, the Green Revolution was a big success. But even there, it came at a cost. Because farmers were expected to invest more in their crops, they had to take out loans. One bad harvest could ruin someone.

At the same time, the high yields began to taper off because of soil degradation. Water sources were polluted by the fertilizers and insecticides. By the 2000s the Green Revolution had left a mixed legacy in India. Whilst many celebrated its early successes, there was also resentment over the pressures placed on small-holder farmers.

Farmers were in more debt and increasingly dependent on foreign multinationals who sold the seeds and fertilizers they needed to stay competitive. Punjab province, often used as an example of the Green Revolution’s achievements, continues to boast a disproportionately high suicide rate amongst rural farmers.

To begin a Green Revolution in Africa, Gates helped create AGRA (the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa). AGRA aimed to double 30 million farmers’ yields and incomes by 2020. To do this it offered to subsidize new technology and practices.

Always thinking in terms of networks, Gates looked to create another ‘loop’. The Foundation bought shares in the US agricultural giant Monsanto in 2010. Monsanto has since had a privileged seat at the table when planning AGRA policies.

In Malawi, for example, an ex-Monsanto executive drafted a new seed reform policy which proposed making it illegal for farmers to save, exchange, or sell their seeds. Apart from being completely impossible to police, this proposal would have further boosted Monsanto’s sales of maize seeds in the country.

Although African governments worked alongside AGRA, many aspects of the organization's approach threatened to reduce agricultural sovereignty. Much of its funding was directed to agricultural technology companies in Europe and America. Small-scale farmers were marginalized in this vision of the future. Large-scale industrial agriculture was the way forward.

Those disturbed by Gates’ disproportionate influence and lack of accountability might have looked to other international bodies for support. But just like with vaccines and the WHO, Gates’ network had the whole thing stitched up. The Gates Foundation is one of the top five donors to the World Bank’s Enabling the Business of Agriculture programme. A programme increasingly advocating for large-scale land acquisitions in the African agricultural sector.

Perhaps it's good news that after almost 20 years AGRA has little to show for itself in terms of impact. The body has refused to make its own monitoring and evaluation data public. However, using government data Timothy Wise has calculated there has been just a 29% increase in maize yields in AGRA target countries (significantly below AGRA’s goal of 100%). Other staple crops are even lower (just 18%). In addition, malnutrition has increased by 30% in these countries since AGRA started operating.

The connection between AGRA policies and famine came under scrutiny during the 2023/24 Zambia drought. Low on forex, the Zambian government sold some of its maize reserves the year before, worsening the effects of the famine. However, the food shortage was also connected to problems in the country’s agricultural sector.

Before the famine, AGRA’s policies in Zambia were connected to increased debt for farmers who struggled to repay loans for fertilizer and hybrid seeds they were pressured into buying. When drought hit in 2024 another problem emerged. By subsidizing maize production and discouraging crop diversity AGRA made Zambia’s drought significantly worse. Yields for climate-resistant crops like millet fell by 24% in AGRA’s target countries. Effectively, farmers were discouraged from hedging their bets.

Researchers also found significant problems with soil health in Zambia. By encouraging intensive farming of one crop, maize, the quality of soil had begun to degrade. AGRA’s best practice recommended planting maize one year, and a less demanding crop the next. However, most small-scale rural farmers simply didn’t have enough land to do this. Traditionally farmers would use intercropping (planting maize with pumpkins for example). This however was not encouraged by AGRA as it limited the maximum potential of maize yields.

Finally, synthetic fertilizers subsidized by AGRA were found to be damaging the soil, leading to acidification and an increase in pests. Zambia’s half-hearted attempt to industrialize the agricultural practices of rural farmers was a disaster. The African Centre for Biodiversity went on to recommend a return to organic composting and mulching, the use of intercropping, and adoption of agroecology (a more holistic approach which thinks about farming as part of a wider ecosystem).

The same weaknesses and pitfalls which have dogged Gates’ healthcare interventions, also undermine his work in agriculture. Over reliance on international networks which marginalize rural Africans. AGRA has actively tried to lock farmers into cycles of dependency on Western industrial agricultral companies.

Gates famously remarked that GM crops would end starvation in Africa. This belief in the ability of technology to override the reality of entire ecosystems makes sense if you’ve spent your life working with microchips, code, and production lines. But anyone with experience in conservation or land management will tell you there are hidden balances and infinitely complex systems in the natural world. Even small changes can have a ripple effect.

Whilst Gates’ vaccine funding has probably saved more lives than it has endangered (although this doesn’t negate the problems with it!), on balance his impact on African agriculture falls more firmly into the negative. At least adoption of AGRAs policies has been somewhat limited.

Why does Bill Gates love Africa?

The Gates Foundation’s impact stretches far beyond healthcare and farming. It has worked with charities like the International Justice Mission for example (you can read our article about their activities in Africa here: The Worst Charity in Africa?).

But why has so much of Gates’ focus been on Africa? He certainly seems to enjoy ‘helper’s high’, the positive feeling gained from assisting others in need. He probably enjoys receiving medals and being praised by the continent’s great and good. But Africa also offers Gates the most pressing needs. The most extreme situations. The most extraordinary contrast between his extraordinary wealth and desperate poverty. The perfect backdrop for his media interviews in the West.

Because, remember, most of Bill Gates’ media funding stays in Europe and America. The Foundation was created at a time his image desperately needed a relaunch. In terms of safeguarding the charity’s reputation, Africa is the perfect continent. After the HPV vaccine roll out went wrong in India, the government there launched an investigation. No such investigation has been forthcoming from African governments following the recent malaria vaccine trials where there was a lack of informed consent.

Gates knows his reputation, and that of the Foundation, needs to be defended in the international press, hence the $319 million donated to media organizations. But in Africa, his targets have little to no voice on the global stage. They simply suffer and receive what is given to them. The perfect beneficiaries. Perhaps this explains the striking disparity between donations to Western and African media groups.

So as Mr. Gates announces plans to give away a further $200 billion, it should be understandable there are mixed feelings on the continent. This likely means more international networks which somehow miss out the crucial reality on the ground. More tech-utopianism which fails to recognise its own limitations.

It also likely means more awards for Bill Gates. More softly lit interviews with the BBC. And more opportunities for a US software engineer to lecture Africa’s pregnant women.

Sources (others linked in text):

https://www.thenation.com/article/society/bill-gates-philanthropy-misanthropy/

https://newint.org/features/2012/04/01/bill-gates-charitable-giving-ethics

https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2025/6/13/sorry-mr-gates-your-billions-wont-save-africa

Excellent article as usual. Gates also received a national award from former Senegalese president Macky Sall at the Grand Challenges event in Dakar in 2023.

It is impossible to overstate Gates' influence in Africa. He is basically a roving head of government whose tentacles reach every nook and cranny. Nigeria's president met with him in the same room where he meets with his cabinet, which should tell you the regard with which Gates is held.

I'd have loved to see an analysis of the report that the Gates Foundation was seeking immunity in Kenya. But otherwise, good work.

Thanks for the article! It's hard to find anything about Gates that isn't too biased either way.