Mr. Beast and the Africa Union

If you look at the most popular videos about Africa on YouTube, you’ll see a big focus on poverty. In a recent video, the Mr Beast philanthropy team hands out wads of cash in a rural village in Uganda. ‘For hundreds of years these people have not had opportunity, but now going forward they have opportunity’, gushes a Mr Beast employee. It’s as if before Mr Beast arrived, nothing was happening in that village.

And perhaps that’s how it should be, some might argue. Africa is a poor continent. So, why in the world is the African Union planning to create a Space Agency? Shouldn’t the AU also be handing out money, or at least building schools? What does outer space have to do with Africa’s problems?

In fact, through history, many African cultures have studied the stars; measuring the seasons and structuring their societies around the rhythms in the sky. More recently African visionaries have started their own private space programmes. In the 21st century, states from Kenya to Egypt are scrambling to form space agencies. Data from satellites track disasters, monitor conflicts, and even help improve agriculture.

For thousands of years Space has played a role in African societies. This is a history of opportunity and investigation: the story of why Africa needs a Space Programme.

Ancient Astronomers

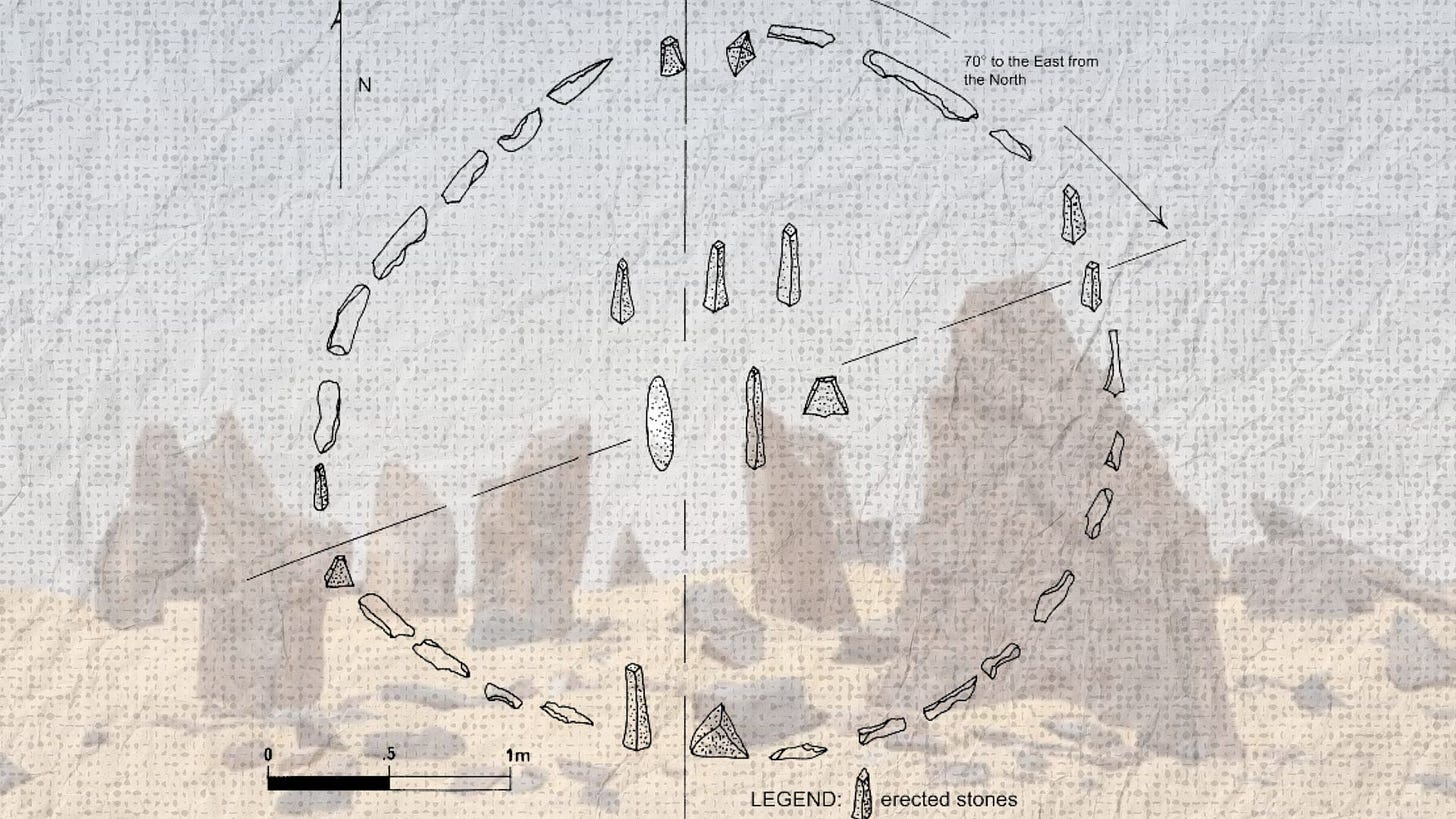

6000 years ago, a group of herdsmen in southern Egypt gathered together to create a stone circle. Each pillar pointed to a bright star in the sky. And the herdsmen could mark the seasons by the way light shone on the ancient stones.

Africans’ fascination with the stars, moon and sun continued long after the monument at Nabta Playa. A few thousand years later the Borana people in eastern Kenya built their own astrological site (Namoratunga II), each pillar pointing to a star to help mark the difference phases of the moon. Like a physical monthly calendar.

In the 1500s astronomers in Timbuktu found that by carefully observing eclipses of stars and planets they were able to judge their distance from the earth. They correctly determined the moon was nearest the earth. And Jupiter was further away than Mars.

In Western media, the most famous African astronomers remain the Dogon people in Mali. In the 1940s, the Frenchman Marcel Griaule tried to write down Dogon beliefs about the stars. He was surprised to learn that the elders believed Sirius, the brightest star in the sky, was in fact three separate stars. With a powerful telescope, it’s possible to see Sirius is two stars in orbit. But the Dogon didn’t have these.

Despite being off by one star, this particular belief sprung a wealth of conspiracy theories. Were the Dogon contacted by ancient aliens? The tragedy of Africa’s history of astronomy is that Western conspiracy theorists keep rewriting the story. It’s as if they don’t believe Africans are capable anything. So, they make up aliens instead. This attempt to exclude Africans from space exploration dogged early visionaries on the continent.

Africa’s Wild West

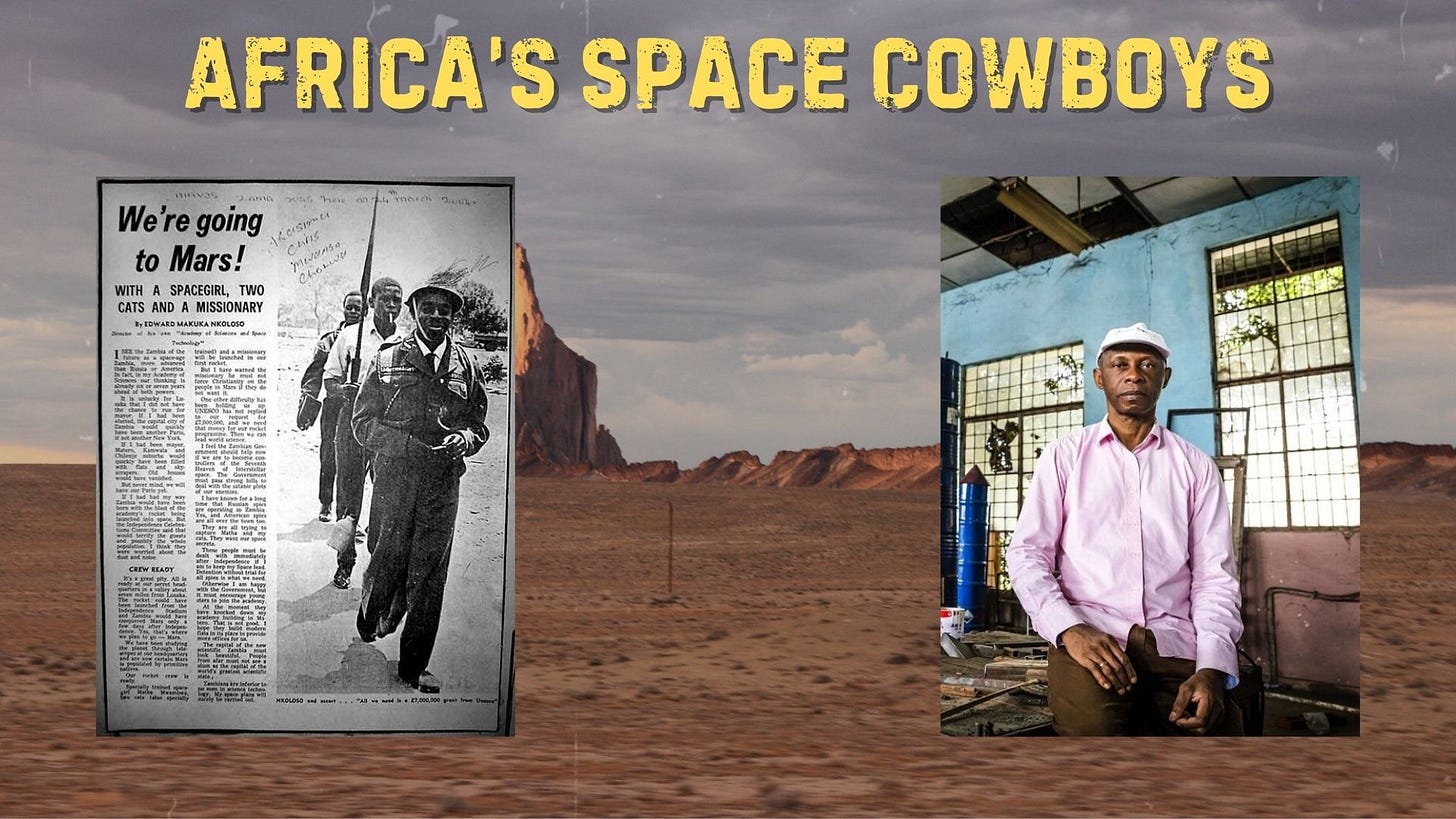

Most explorers are a little bit mad. Edward Nkoloso probably fits that description. Born in 1919, when Zambia was still under colonial rule, Edward fought in the resistance before he was arrested and imprisoned. When was finally released he had a clear goal. Whilst other Zambians rushed into politics, Edward set up a National Academy of Science. Then he began promoting his Space Programme. Shunned by the Zambian government and mocked by the international press, he remained serious about his vision. He searched in vain for billion-dollar international funding.

Edward envisioned Africans being the first people to arrive on Mars. He also wanted the first astronaut to be a young woman, accompanied by a Christian missionary under strict instruction to respect any aliens they found. There would be no colonial-style forced conversions. Unlike the macho fighter pilots who manned the first space missions, Edward imagined a very different journey of discovery; one where ‘Afronauts’ replaced Americans.

Ultimately the massive funding needed for the programme never materialized, and Edward moved on to other projects. Like the popular Congolese scholar Eddy Malou, a lot of people made fun of him. But a few caught onto his vision.

In 2007 Jean-Patrice Keka started building a series of rockets on an empty plot of land, outside Kinshasa, DRC. The troposphere project was more achievable than Edward’s Martian dream. After three experimental launches, Keka invited some government ministers to observe his rockets. Troposphere 4 reached a maximum altitude of 16 kilometres after just 47 seconds. Impressed, the government agreed to offer a little support to the project.

Keka’s fifth rocket fired a small rat into the atmosphere but sadly went off course and crashed, killing the rodent. Undeterred he began crowd-funding a sixth rocket which aimed to reach outer space and deploy a small satellite. The launch of the sixth rocket has been repeatedly pushed backed over the past decade.

The most impressive part of the Troposphere project is the low level of technology. Computers from the early 2000s are used to launch the rockets. They are made from materials bought in markets in Kinshasa.

From the 1960s to the 2000s African space exploration was a bit like the wild west. Governments weren’t interested and visionaries with big dreams and limited resources took on the challenge. But this has now begun to change.

An African Space Programme?

Recently, over 20 African countries have set up national Space Programmes. Kenya for example, has launched two small cube satellites since starting its space agency in 2017.

Algeria has a well-funded space programme and has several satellites in orbit, many used as part of a global disaster monitoring system. When floods or fires occur, these satellites provide high quality images to help relief organisations and governments.

Egypt has launched some of the largest African satellites in orbit, and Cairo is now the headquarters of the Africa Space Agency.

But its newcomers, like Rwanda, who look like the future pioneers of space in Africa. Founded in 2021, the Rwanda Space Agency is trying to buy existing satellites from private companies. Each year African governments spend millions buying data about the continent from satellites. The RSA has its eye on making a profit from space.

Just as the stars guided African farmers in the past, modern satellites have become vital in predicting problems. In Kenya and Ethiopia, enormous locust swarms sweep through fields, devouring everything in their path. Climate monitoring satellites track soil moisture, rainfall and cloud cover, to predict when and where a swarm will appear. Meanwhile, GPS mapping has made tracking the swarm much more accurate. In 2021, $1.5 billion worth of cereals and milk was saved from locust swarms thanks to satellite data.

More and more governments are realising that Africa needs to invest in Space to address problems on earth. But there are still many barriers to overcome.

At present African satellites are launched by foreign rockets, and usually deployed from the International Space Station. It’s this technology gap which the African Union’s Space Programme is looking to overcome. Africa needs to invest in its own rocket technology, manufacturing, and research.

Once African satellites are being deployed from African rockets, we will be able to say that for thousands of years space has been part of African societies, and now, going forward, it will continue to be.

Sources

https://www.earthranger.com/success-stories/fao

https://servirglobal.net/news/could-satellites-help-head-locust-invasion

https://www.rmg.co.uk/stories/topics/zambian-space-programme

https://spaceinafrica.com/2020/07/01/astronomy-in-africa-the-past-the-present-and-the-future/

https://www.unoosa.org/oosa/en/ourwork/space4sdgs/index.html

https://www.endurosat.com/news/taifa-1-kenyan-nanosat/

https://www.space.com/935-ancient-african-skies.html

https://edition.cnn.com/science/african-space-agency-tidiane-ouattara-spc/index.html

https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/37434-doc-au_space_strategy_isbn-electronic.pdf