The Protest that never happened

In February, hundreds of activists took to the streets across France to protest ‘Bollore’s Empire’: the sprawling media-business conglomerate owned by Vincent Bollore. They smashed paper mache copies of his head and shouted about his ‘colonial’ behaviour in Africa.

At the same time, very cordial negotiations were taking place in Johannesburg, where Vincent Bollore was bidding to add Multichoice (including DStv) to his media empire. Positive noises were made about black empowerment. The government regulators allowed the deal to go through. With hardly a whisper Vincent Bollore was going to control the main TV subscription services in both Francophone and Anglophone Africa. The takeover looks set to be finalized by October.

Vincent Bollore is not viewed as a coloniser in South Africa. In fact, thanks to the press language barrier very little is known about him at all. The critical voices that have emerged draw in a handful of American articles which compare Bollore to the media tycoon Rupert Murdoch. Bollore is a conservative, supporting candidates like Marine Le Pen. Perhaps his takeover will open the door to more far right voices?

In fact, the situation is much worse than this. Bollore is famous in France for his corruption scandals and attacks on critical journalists. He has supported West African dictators, influenced elections in exchange for contracts, invested in exploitative plantations, and sued anyone who complains about it. If the Multichoice deal is done, it could have serious political consequences for Africa as a whole, and the Bollore group will have effectively monopolised TV subscription services across the continent - barring Arabic speaking countries.

What’s crazy is that Bollore is not even that rich. His fortune has rarely surpassed $10 billion. But his careful planning has allowed him to maximise his political power in Africa. This is the story of how a French family built an African media empire.

The beginning of an empire

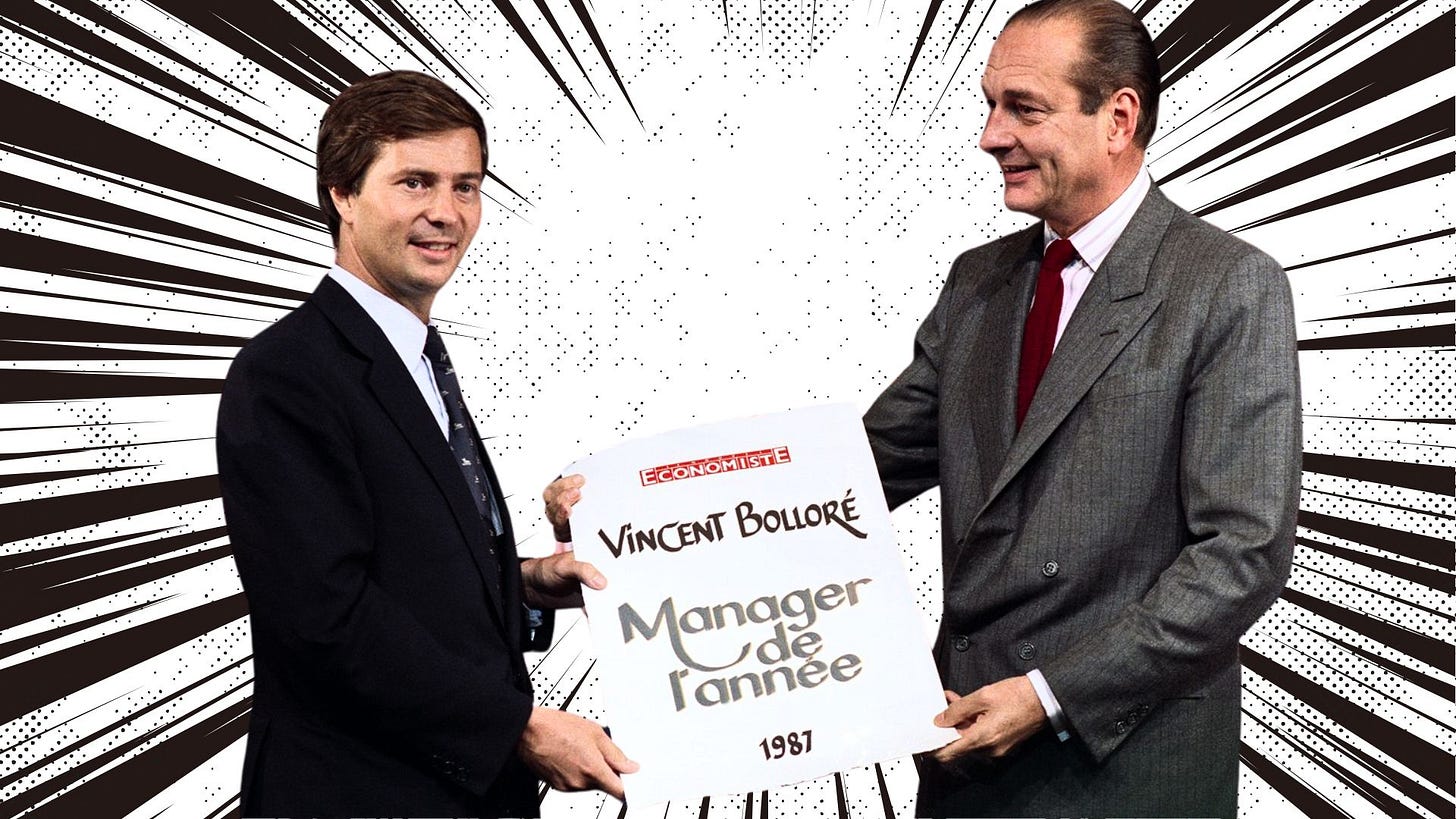

Vincent Bollore was born into a Breton business family with connections to the Rothschilds. His parents had made their fortune with a paper business, specializing in thin sheets for Bibles and cigarettes. By the 1970s the business was on the edge of collapse. Secularization and the health hazards of smoking threatened to ruin the family. Using money earned as a banker, Bollore bought out the business for two francs.

Standing on a pile of palettes on the factory floor, the 29 year old promised to not fire any staff on the condition they agree to a reduction in salaries. His charm and apparent sincerity carried the day. Bollore Paper Makers, became a plastic sheet manufacturing business.

By 35 Bollore had turned the failing business into a booming industry exporting to the United States. Profits from plastics were invested into new ventures, including ports and the energy sector. Within ten years he was a billionaire. The newspapers called him the ‘Prince of the Cash Flow’.

The African Profit Margin

‘I will personally intervene in everything we have discussed’, Bollore told a crowd of activists in the 2010s. Africa was like a drug to the Bollore empire. From the 1980s investments in Africa brought the biggest profit margins. By 2017 roughly 80% of the Bollore Group's income came from businesses on the continent. For an ambitious French businessman looking for lucrative investments on the cheap, African ports and plantations were impossible to ignore. However, like every drug there was a cost: for Bollore, it was his reputation.

The Africa investments started early for Bollore. He would typically invest a little at first. Then gradually over five or ten years buy enough shares to establish a controlling stake. In 1986 he took a stake in SCAC, a shipping company with Africa links. By 1988 he started to invest in the Rivaud Group which controlled massive plantation holdings in West Africa.

In public Bollore gave these activities a veneer of ‘development’. Africa, he claimed, was the ‘Korea of the twenty-first century’. Careful observers noticed many of the countries he was investing in were former French colonies, and the industries and infrastructure he was taking control of were created during the colonial era.

By 1990 Bollore had a significant stake in Coralma which had a de facto monopoly on the buying and selling of tobacco in Madagascar, Senegal, Gabon, Chad, and the Central African Republic. Comprising just 5% of the Bollore group’s activities, Coralma supplied 25% of its total profit in 1993. Like Unilever, Bollore discovered a lot of money could be made from African consumers.

For the expat staff employed by Bollore in Africa there was a sense of adventure. A frontier spirit. Staff were encouraged to search out new opportunities, take initiative, and discover pockets of potential profit. Ange Mancini, a former French policeman who Bollore employed to run a railway in West Africa, would describe the company culture as ‘a camp of gypsies’.

Outrage over Bollore’s Africa activities soon manifested in France. Protestors were less worried about the cigarette sales and more concerned about child workers and deforestation on the plantations. By buying the Rivaud Group in 1996, Bollore had acquired a controlling stake in SOCFIN, a massive multinational palm oil plantation company with Belgian colonial roots. SOCFIN has tens of thousands of hectares under its control in Ghana, Nigeria, Sao Tome, DRC, Ivory Coast, Liberia, and Sierra Leone. However, it is in Cameroon where SOCFIN’s power is greatest. There it had a quasi-monopoly on the buying of palm nuts, with small scale farmers often intimidated by plantation security staff.

Uncovering the crude roots of Bollore’s profits was not hard. French journalists simply had to fly into Cameroon and talk to a couple of informal labourers on a palm oil plantation. What they found was unsurprising. Poverty, no safety equipment, some young teenagers, and stories of abuse.

Unfortunately, this Western outrage was somewhat misplaced. Bollore had a major investment in SOCFIN, but he had not created the Cameroon plantations. He was making money from a pre-existing system of oppression. His truly nefarious activities took place behind closed doors.

It's in the logistics sector that the Bollore Group showed itself to be an active menace to the continent's development. From 1999 Bollore began building a transport empire which would eventually cover over 40 African countries and include 15 ports.

Winning competitive bids to run West Africa’s shipping is not easy. Many companies would like to run the Atlantic ports, which supply landlocked countries in the Sahel as well. Bollore gained an edge by appealing to the selfish concerns of his African contacts: politicians with short-term thinking and greed and power on the brain.

In Guinea, Bollore offered to help President Alpha Conde win the 2010 elections in exchange for a favourable port deal. Euro RSCG, a political consultancy owned by Havas, a Bollore Group media company, was subcontracted to advise Conde’s campaign. Bollore looked to have gotten away with this very illegal behaviour until another company sued him for their losses due to this action. He was given a slap on the wrist and ordered to pay 2.1 million Euros.

In Togo, Bollore offered a similar ‘votes for ports’ deal to authoritarian leader Faure Gnassingbe, who was also worried about upcoming elections. This one came back to bite Bollore. Ten years later a court in France would try him for the bribery and election interference. Despite intially agreeing to a plea deal, the judge was so outraged at Bollore’s behaviour she rejected the settlement and ordered a full trial. The case is ongoing.

Andrew Weir has shown how even in less famous cases, for example Ghana, the actions of the Bollore Group continued to skirt the margins of legality. In this case Bollore avoided the bidding process altogether, secretly contacting President Mahama in 2014 and agreeing a deal in private. Sources suggest Bollore’s Ghanaian associate agreed to subcontract some of the work to an engineering company run by the president’s brother. The port deal in Ghana was so unfavourable to the government that the next administration was forced to renegotiate it. Bollore generously allowed the government to buy back shares at an exorbitant price.

It was in Africa much of Bollore’s fortune was forged. In Africa he grew his wealth from a few billion to almost ten billion. He used former colonial business networks to expand his influence at first. Later he learned to work with selfish local politicians to strike favorable deals. However, the reputational cost has been heavy. Court cases and protests dog Bollore and his African empire. In recent years he has tried to cut links between himself and the ports. Bollore Logistics was taken over by his son Cyrill and finally sold off for a hefty profit.

Perhaps Vincent Bollore’s greatest weakness is hypersensitivity about his reputation. French journalists who investigated what was happening in Africa were intimidated and threatened with legal action. Some were sued. Bollore even argued that plantation workers who claimed to be underage were lying. It should be no surprise that as Africa operations drew heat, Bollore increasingly invested in media companies to control the narrative about his behaviour.

Media Convictions

‘Don’t spit on the hand that fed you… shut up you jerk… you piece of sh*t!’

Not many TV presenters can get away with language like this, and Cyril Hanouna was quickly handed a hefty fine (3.5 million Euros) for his treatment of left-wing politician Louis Boyard.

The 2022 debate on Don’t Touch My Set was supposed to be about migrant rights. Instead, a small comment referencing the Bollore Group in Africa quickly spiraled into a ten minute shouting match. Hanouna unshakably defended Bollore, shouting over Louis Boyard and accusing him of being anti-French, a liar, and disloyal.

Behind the explosion of passion lay a darker reality. C8, the channel which broadcast the show, was owned by the Bollore group. In fact, Don’t Touch My Set was the brainchild of Cyril Hanouna and Yannick Bollore, one of Vincent Bollore’s sons. Part of Cyril Hanouna’s anger came from the fact Louis Boyard had started his career in Bollore-owned media before transitioning to politics. Now he was ‘spitting on the hand that fed him’.

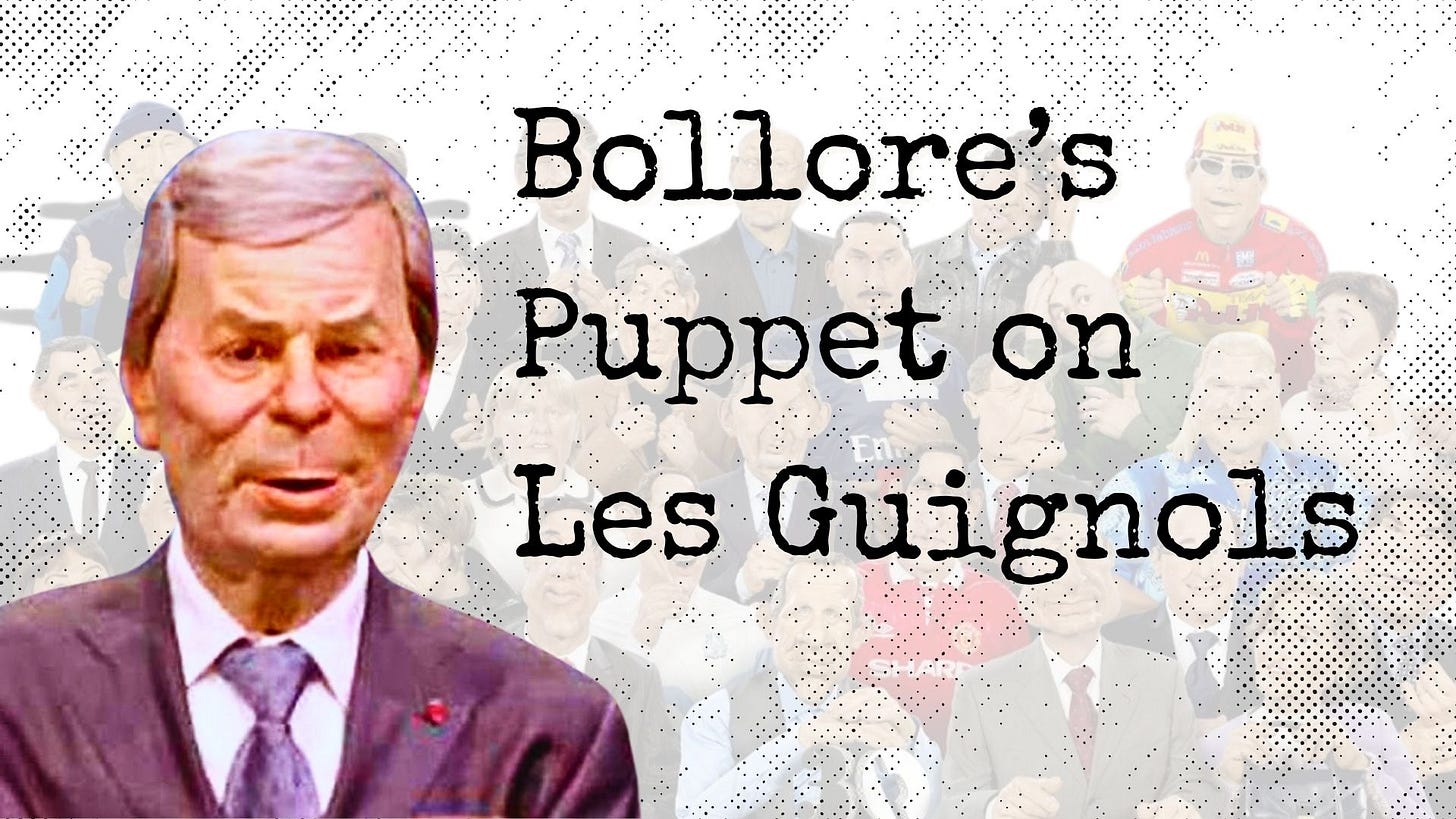

Bollore had been investing in media from before 2010, buying shares in Vivendi and Havas. His presence became more noticeable in France when he took direct control of Canal+ in 2015. Writers on satirical shows who had mocked Bollore in the past, for example Les Guignols, were immediately fired. The political puppet show was removed from prime time. Its staff desperately fought to keep it alive, even proposing a sketch praising Bollore. However, by 2018 the long running show was fully cancelled.

The writers of Les Guignols weren’t the only people upended by Vincent Bollore. Two journalists investigating Bollore’s impact on the media were visited by a bailiff demanding 700,000 Euros compensation simply because they had requested an interview.

This attempt to censor or intimidate critical voices was not confined to France. Canal+ Afrique is a major TV channel across Francophone Africa. In 2017 it released a documentary titled Togo: Leave the Throne. The documentary chronicled the spontaneous protests against Faure Gnassingbe’s government which were brutally crushed by police. The Gnassingbe family has ruled Togo since 1967. They are also key contacts of Vincent Bollore who benefited from a generous Togolese port deal.

Several days after its release the documentary was removed from all Canal+ channels and the website. Apparently ‘instructions were given internally’. Two employees were also fired. An anonymous source told Reporteurs Sans Frontiers that staff were told: ‘From now on at Canal, we don’t talk about wealth, we don’t talk about banks, we don’t talk about Africa.’

Alongside this censorship drive, was a new political slant. As a young man Bollore had proved a pragmatist, forging connections with politicians on the left and right. Now he seemed to favour the right. In the build up to elections in 2022 Cyril Hanouna invited candidates like Eric Zemmour and Marine Le Pen onto his show.

Parts of the French establishment were horrified. ‘These are the two realities of the Bollore system’, commented media historian Alexis Levrier, ‘the classic journalism of the extreme right incarnated by Eric Zemmour and the horizontal populism represented by Cyil Hanouna… the horizontalism which prioritizes the clash normalizes the ideas of the extreme right’.

Bollore’s romance with the right eventually landed him in hot water. By 2025, C8 was simultaneously France’s most controversial and popular TV channel. Two million viewers regularly tuned in to Don’t Touch My Set with Cyril Hanouna. However, as Hanouna gave a platform to far right voices he earned the ire of France’s TV regulator. In just a few years Hanouna had received tens of warnings and fines. In February 2025, C8 was banned.

There was widespread outcry on the right. A feeling that freedom of expression was being targeted. But many journalists were strangely quiet. Perhaps some relished the idea that Bollore the bully was finally getting a taste of his own medicine. The censor had been censored.

Bollore’s political shift right is something of a mystery. In his business deals he had always been a pragmatist. In dealings with the media his biggest concern has been his personal reputation. So why has he picked a side? Bollore is a proud Breton and committed Catholic. Perhaps he simply feels able to express his beliefs more openly now he has so much power. Or perhaps, by choosing a side he has found a political cause, a popular cause, which will redefine his image in France. Yes, those pesky anti-fascists will keep protesting about plantations, but activists on the right and far right will talk about him as an ally for the cause.

Bollore was always careful with the media. As he has grown older he has done fewer and fewer interviews. And so journalists are left to speculate whether the move right is the result of long held ideology, or another pragmatic strategy to secure his fortune and protect his reputation. Perhaps it's a little bit of both.

A Pirate or a Gypsy?

Ex-cop Ange Mancini would remember Bollore as ‘the King of the Gypsies’ in Africa. All things were permitted for profit as long as everyone was loyal to Bollore.

An anonymous employee of Canal+ told a journalist:

‘Bollore has the right of life or death over his subjects. It’s insane. Either you leave with a cheque or keep your head down and he makes you rich.’

Depressingly, Bollore’s immense success in Africa has only been possible because corrupt leaders with short-term thinking have chosen to do deals with him. Far too many elected politicians in Africa have been content to ‘keep their head down’ and become rich.

Francois Holland gave a darker analysis: ‘ I think we should distrust Bollore. Not only politically. Those who have not distrusted him are dead. He’s a pirate.’ Rival billionaire Martin Bouygues described him as ‘a thug. He rooked me, tricked me, and humiliated me. I will never forget it’.

This dark side to the Catholic Breton earned him a famous nickname: ‘the smiling killer’. He was, most of his enemies agreed, a liar.

In a rarely candid interview in his office in 1999, Bollore showed his guest a framed photo on his desk. It depicted a man being eaten alive by a boa constrictor. ‘That is reality,’ he said calmly, ‘That man was unlucky enough to fall asleep in the forest. Then he was eaten.’

This ruthless, two-faced, willingness to do anything to get ahead is what allowed Bollore to turn a failing paper company into a post-colonial business empire. He has largely achieved this by appealing to the crudest aspects of the people around him. Hunger for wealth and fear of angering him.

His extraordinary drive led two French sociologists to use him as a case study in their 2005 book Portrait of the Businessman as a Predator. These heroic business figures actually specialize in exploiting areas of unequal power or economics, argued Michel Villette and Catherine Vuillermot. In this context, Bollore's attraction to Africa makes a lot of sense.

Unfortunately he has not mellowed with age. In 2018 one of Bollore’s associates told a journalist his controlling behaviour had gotten worse.

‘These last years I have seen him transform, becoming more and more authoritarian and entering into a kind of all-powerfulness. Bollore today is like Louis XIV and his royal court.’

In the light of all this, everyone must ask themselves seriously if Vincent Bollore is someone they want running their media. If the deal does go through they can expect censorship, political favouritism, coverage which benefits dictators, the decline of satire, and so much more! All coming to DStv in October, broadcasting from Nigeria to South Africa, and everywhere in between.

Sources (others linked in text):

https://www.bollore.com/en/le-groupe/history/

https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/economie/030209/comment-vincent-bollore-s-est-taille-un-empire-en-afrique

https://multinationales.org/fr/enquetes/le-systeme-bollore/les-rentes-africaines-de-bollore

Nicolas Vescovacci et Jean-Pierre Canet, Vincent tout-puissant, (2018)

Hmm just like The Merc wrote about months ago. Maybe we shall protect our Media cause we don’t control our narrative. Even tv programs are mostly foreign instead of Local.

Interesting read. I never even knew about him. DSTV has not been performing very well in SA so he can have it.